Decentering Colonial Narratives About Zimbabwe

The military coup and the situation going on in Zimbabwe right now made me reflect on my childhood growing up in Robert Mugabe’s Zimbabwe, when fear was our daily bread and suffering our dessert. And we had someone to blame: the white man. In this article, I will draw from my personal history to shed light onto the current state of Zimbabwe. In addition, I will highlight how Western scholars and the media’s take on this coup highlights nothing else but an old condescending attitude that disregards and diminishes African agency: the belief that Africans are always pawns who are being pushed around by either super powers or forces of globalization. The Western tendency to constantly look for external influences when approaching African issues is dated and malignant. Journalists and scholars should have abandoned this notion on the first day they decided weren’t racist. For good or for ill, the Zimbabwe military coup is first and foremost the doing of Africans and should be approached as such! I argue that Zimbabweans are so desperate for change that they could replace Mugabe with anything, even a dangerous ‘crocodile’ like Mnangagwa.

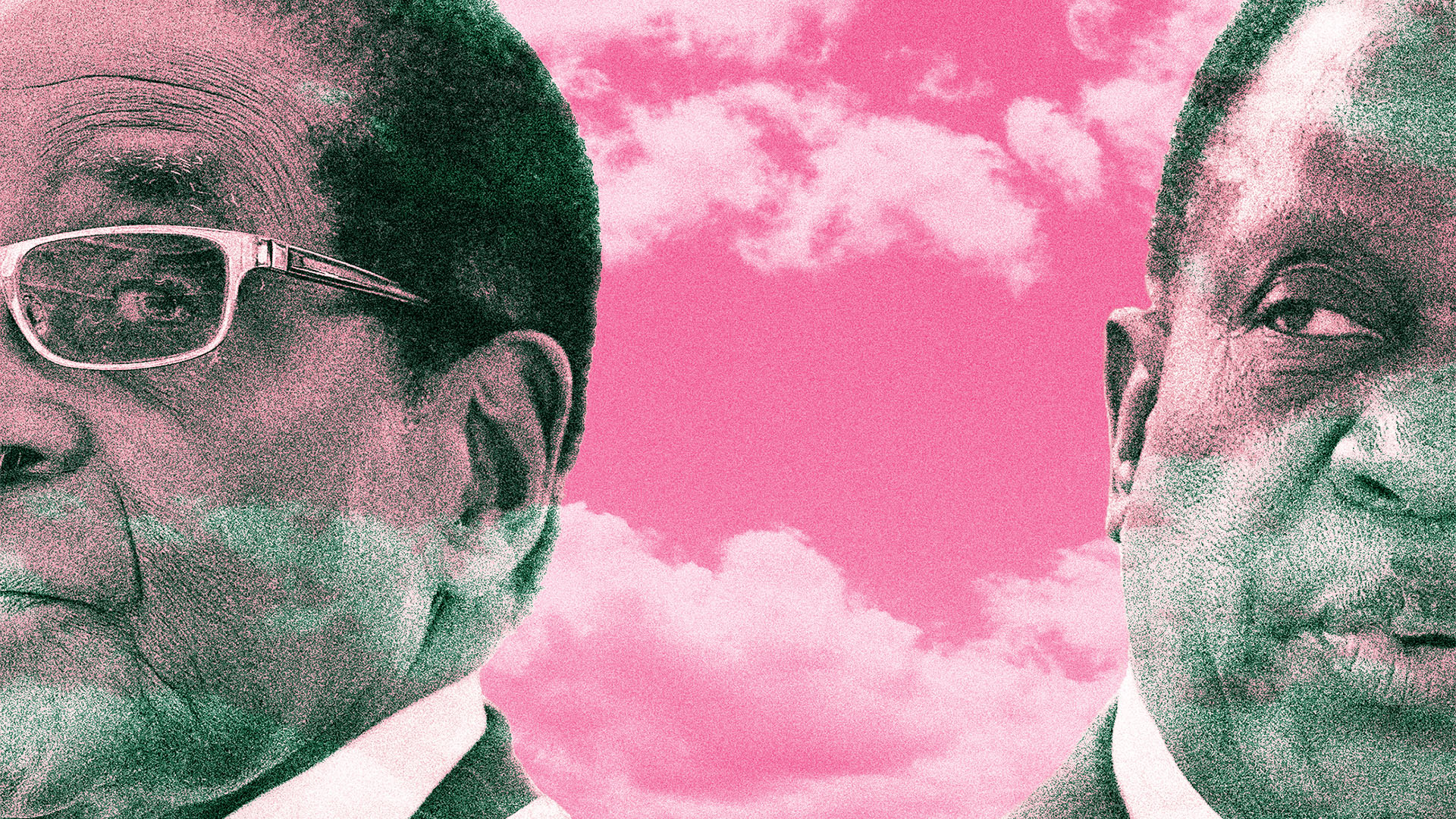

Zimbabwe gained its independence from Great Britain in 1980, and Robert Mugabe has ruled the country with an iron fist since then. During the guerilla war of liberation from Britain, Emmerson Mnangagwa was one of the leaders of the guerilla fighters and through this he won Mugabe’s trust and has remained loyal to him ever since. This made Mnangagwa’s ascent to the vice president’s position predictable. Their relationship soured when Mugabe’s wife, Grace, declared her intention to succeed as President in competition with Mnangagwa. It was Grace’s aspirations that triggered the coup, as it is believed she manipulated her husband to fire Mnangagwa. One thing that unites all the characters in this plot is their shady history.

We were the only ones with a radio and a black and white television in our village. I recall sitting under the moonlight in 2002 on election day. Many of the villagers came to our courtyard. I was used to this as every Sunday afternoon men would come to squatter around the supersonic radio set we had and listen to football. This day, however, was different, even women came down despite it being the night. They began the night by writing down all the constituencies in the country; getting ready to record the numbers who voted in each constituency as the results were announced in between anti-colonial and liberation struggle songs mainly by Cde. Chinx Chingaira and Cde. Elliot Manyika. The moonlight of fear is how I remember the night; as an eleven year old I was made to believe that if Mugabe’s rival, Morgan Tsvangirai were to win, then the next day the brutal white people would immediately come with helicopters to bomb us and take away our land.

Bulawayo is a city inhabited by the Ndebele minority ethnic group, the city has always voted for the opposition in elections. It used to boom with industries during the colonial period but a move by Mugabe to remove industries to Harare left a lot of Ndebele people feeling disenfranchised. Conspiracy theorists even speculated that if the whites were to colonize Zimbabwe again, they would start in this most anti-Mugabe city where they would face less resistance.

The army general then was Vitalis Zvinavashe, another commander who fell from grace when he was suspected of planning a coup. The same happened to his successor, Solomon Mujuru, who was later killed by Mugabe. In 2002, Zvinavashe threatened people against voting for the opposition. My family was in fear not only of the white people who would come and take over, but also of the ruling party’s youths (ZANU-PF) who were boasting that they had been given permission by Zvinavashe and Mugabe to rape, torture and kill anyone who sold the land back to the whites through the ballot box.

On this night, the villagers had no other choice. “ZANU-PF wins Nembudziya”, came the announcement from the radio at around 2am. Claps, ululating and whistles of relief filled the atmosphere. Nembudziya district had just gone through a terrible famine which left people hopeless, the election really mattered. I had also learnt that the general of the army had supposedly threatened that the constituencies which voted for Tsvangirai would be cut off from the indigenization program. This was the program of taking away land and resources from white settlers and giving them to Africans who participated in the war of liberation.

Tsvangirai had been openly labelled as the greatest traitor and associating with him was the biggest sin. I recall one day, my brother and I were riding a scotch cart to fetch water from the river. We had woken up so early, we had to save kerosene as it was becoming more and more expensive. In the early hours of the morning we didn’t light up the kerosene lights, so I dressed in the dark and wore my shirt inside out. We then bumped into ZANU-PF youths who took my dress code as a political statement to mean ‘change’. They harassed the puberty out of me for this innocent act. ‘Change’ was the most forbidden word and was in no way allowed to be used in any sentence. Not only did ‘change’ imply change of leadership in the country, Tsvangirai’s opposition party was using it as their slogan!

My childhood home was down a road called ‘Boundary Road’. This road got its name during the colonial era. We were staying on the Shona side; across from us were the Ndebele people and the Tonga People. My mother had friends from all sides, she spoke all their languages. I would go visit with her when she was hanging out with her friends on the Ndebele side. This kind of boundary crossing had become rarer after the 80s. When my mother went for business trips she would leave me with her Ndebele friends. I would hear stories of ‘gukurahundi’, a genocide that was perpetrated by Mugabe and his clique. This genocide was done to intimidate the Ndebeles as well as to reduce their population prior to the elections in late 80s. The same threat was being thrown around prior to the 2002 elections. Fear was also the Ndebele people’s daily bread. For some Ndebeles, ‘gukurahundi’ and ‘rova’ were the first Shona words they learnt.

MaNcube was my mother’s very good friend. Despite their different ethnicities, their friendship overcame the ethnic tensions because they shared the same totem: monkey. It was from her that I heard the Shona songs they were forced to sing during the genocide, praising Mugabe and vilifying Joshua Nkomo. It was during these times that I learnt the name Mnangagwa. Mentioning Emmerson Mnangagwa would make maNcube cringe. One night while sitting around the fire roasting maize, she began to tell me to why she had moved up north from where she lived before. “I saw my two brothers walk into that pit…” she said then broke into sobbing. Although I asked her many times, she never told the rest of the story. The furthest she could tell, was when she added “the soldiers walked towards them and lifted a shovel.”

It was later when I moved to Hong Kong and the US government declassified some of the documents related to this time in Zimbabwe that I fully understood what had taken place. That shovel almost certainly hit maNcube’s brothers on the head and they were buried alive in the mass graves which are now being discovered. Mnangagwa, the man some Zimbabweans are hoping would replace Mugabe, is supposedly behind this genocide.

The Mugabe regime had painted white people as the most brutal animals on earth. Seeing them being kicked out of their farms and businesses or being tortured seemed justified. In fact, any form of physical and structural violence against white people seemed justified. It was only some years later when I moved to study in the US that I realized all my life had been an illusion. Growing up I was given a sense that Americans and the British were all losing sleep finding loopholes to colonize Zimbabwe and that we should never give them a chance. The anti-colonial rhetoric was so strong that I could recall how as a small boy I would be scared whenever an airplane passed by: “It could be white people”. Many years later, a colleague I met in South Africa, who had grown up on the opposite side of Zimbabwe from me, recalled the times she would hide under the sofa whenever a white person showed up on TV. At the time we were both science teachers in a white majority South African town, and many of our students were white. We were amazed how the whites were just people like us.

When I moved to the US I was shocked! Americans were mostly talking about abortion and transgender bathrooms. Nothing about Zimbabwe and the legendary Mugabe who had made it hard for them to colonize Africa. As a matter of fact, only a few had even heard of the country’s name. Their Capitol Building which I visited some time during my stay in the US had many domestic issues to worry about and it seemed impossible that Congress would lose sleep over Zimbabwe. It was a shock to me. My fear of the white man which I had been raised with seemed to have been an illusion all along.

We were suffering: there was no food, no nothing and a longer life span was now a privilege only rocks had. One wonders why we didn’t fight. Those who had access to food was thanks to diasporic ties. Without diasporic ties one was as good as dead. NGOs were banned from bringing food to us, and even for those NGOs who still brought food, the government officials would take all of it and turn it into a personal business.

In 2008, my brother tried to cross the border illegally, to South Africa. I tried to stop him because the Limpopo river was dangerous to cross in the rainy season. He needed to pay a calf to the smugglers to get across. I objected to the whole idea. I would have rather died from hunger with my brother, than hear that he had become one of those swept to death by the mighty Limpopo. I slept in the kraal, so he couldn’t steal the calf. But one day he managed to sneak out and disappear. Thankfully, the smuggler he paid was a con-artist who just dumped my brother and his other victims in some village in Beitbridge.

Things were so bad, but still a large majority went on to vote for Mugabe in the 2013 elections. One would wonder why? We were told that all our suffering came from white man’s greed who wanted to come and grab all our precious minerals. When a child died in a village from something as preventable as malaria, we would blame it on the sanctions put on by the white men, never on the leadership in the country.

When I was in high school, I spent most of my time around or inside the biggest air-base in Zimbabwe. My high school was associated with the airbase and some of my family members were working in the air force. I recall one event when the new prime minister, Tsvangirai, visited and the leader of the air force, Perence Shiri, refused to salute him. He had his reasons which resonate with the remarks made by the man leading the coup today, Constantine Chiwenga. On the 18th April 2017, Chiwenga declared that he will not salute a 'President without liberation war credentials.'

Many may see this transition after Mugabe as a hope for the country but this background may highlight some of the issues which are necessary to look at. How fear might have festered within many Zimbabweans throughout these years. One thing to be worried about is that there will be no new blood in this supposedly new Zimbabwe after Mugabe. As Chiwenga remarked, without liberation credentials one can not be a president. This has been the entire rhetoric since 1980. Even the legendary hope of Zimbabwe, Joshua Nkomo who is affectionately referred to as father Zimbabwe was delegitimised using false information on how he had not been an active member during the struggle for independence. Mnangagwa has committed genocide, we really have to be hopeless to believe in him!

Many Zimbabweans know that this entire coup is a scam, a recycling of the bad guys. But people have suffered so much that they are willing to settle for anything which could get rid of that tyrant Robert Mugabe and his dangerous wife. Many can’t imagine that there could be anything worse than what we have already gone through. I am confident that even if a donkey had been suggested as a replacement for Mugabe many would agree. Why is this so? Because the suffering has been just too much and for many of my friends they know Chiwenga and Mnangagwa are a terrible idea, but they have rationalized this as a just transition to a new Zimbabwe. Anything that promises to kick out Mugabe is fine, that is how low the standard has gone for many Zimbabweans who are desperate for change. As for me I will not easily forget the things these men have done; the fear they instilled in us and that same fear is what they are riding on today in this coup.

It should be obvious by now that from my personal history, it would be hard to be in favor of either Mugabe or Mnangagwa, ‘the crocodile’. Mnangagwa is obviously riding on the desperation of the citizens and the fear that he himself has helped build. However, the notion that we Zimbabweans can’t possibly have independently worked on this coup is false. The belief that only China or the US can bring down the dictator is very condescending and misguided. Mnangagwa is obviously cut from the same cloth as uncle Bob and no doubt he will be another tyrant. But please, when the desire for change is strong enough, we are capable of replacing a dictator we don’t like with another dictator we also don’t like. My recent encounters with friends as well as with the Western media made me reflect on how the world thinks of African agency.

"Do you think it could be the Americans behind the Zimbabwe military coup?" my Hong Kong American friend asked while wearing a very curious and genuine face. "If the Americans were behind this then it would have been obvious," I responded. He didn't know if he should take me seriously or not, but I continued, "Have you heard of a proverb that “If you wanna find an American involvement anywhere, follow bloodshed.'" Some of my native Hong Kong friends made similar remarks: "I saw on the news about Zimbabwe, is it related to America?"

My patience was already wearing thin by this point, but I lost my temper when my social media contacts started sending me Guardian and CNN articles which claim to have found clues about Chinese involvement in the Zimbabwe coup. But sadly, the clues they have found only point towards their deep and unaddressed prejudices. All these claims highlight, is that the generals involved in the coup had a meeting with the Chinese military. And they infer that these meetings indicate how it's all a Chinese plan, or at least how the African nation wouldn't have gone ahead with the coup without China's permission. Even if it were true, which it's not, making this bloodless and well planned coup about the US or China is rather an indication that many people somehow think Africans never have agency in anything. Not everything is about the US or the so called super powers, and approaching almost every issue in Africa with the mindset of trying to see the traces of a superpower is not only lazy and careless but it is also unjust. It contributes to the literature that misdiagnoses problems African nations face, with wrong 'clues' and 'insights' produced by careless journalists and scholars who aren't willing to invest in understanding African issues for its own sake. This could lead to many other problems e.g spending resources on wrongly diagnosed problems.

I don't care whether it's about good or bad things, I just think anyone who has a tendency to find outside force explanations for anything that happens in Africa should reflect for a second on his/her possible prejudice. Africans are not barbaric pawns who can't do anything by themselves. I am not saying that we should neglect outside influences, what I am saying is that if that is all we study then our insights and clues are doomed to be unscientific and a part of a dated, racist and condescending colonial tradition of studying ‘savage’ societies.

In the end, Mugabe is a tyrant and his wife triggered his inevitable downfall. The people who toppled him have a strong and misguided belief that any new leader would have to have liberation war credentials, and this alone indicates that old and clueless leaders is what we shall have for the next 4 decades as we have had for the past 4 decades. The ‘hope’ of the nation, Mnangagwa, is cut from the same cloth as Mugabe, he has committed many crimes and a genocide under his belt should have been enough to disqualify him, but Zimbabweans are desperate for change. As part of the Mugabe machine for 4 decades, Mnangagwa was an architect of fear and intimidation, and today he is enjoying a free ride on this vehicle which he created. As the masses march and sing to Jah Prayzah’s ‘kutonga kwaro’ - the way a crocodile rules, the tens of thousands of Ndebele people whom he slaughtered are rolling over in mass graves. Oh, how they wish they had been buried with enough room to rollover. We kick out one fear architect and we replace him with another, but still it is our agency. It is time for Western scholars and journalists to radically change their approach to African issues, and acknowledging African agency is a good starting point. If they are not capable or willing to do so, then perhaps consider not commenting on the region at all. Throughout my life, I have learnt that not everything that happens in Zimbabwe is because of white people. White folk, however have yet to learn that not everything that happens in Zimbabwe is because of them.