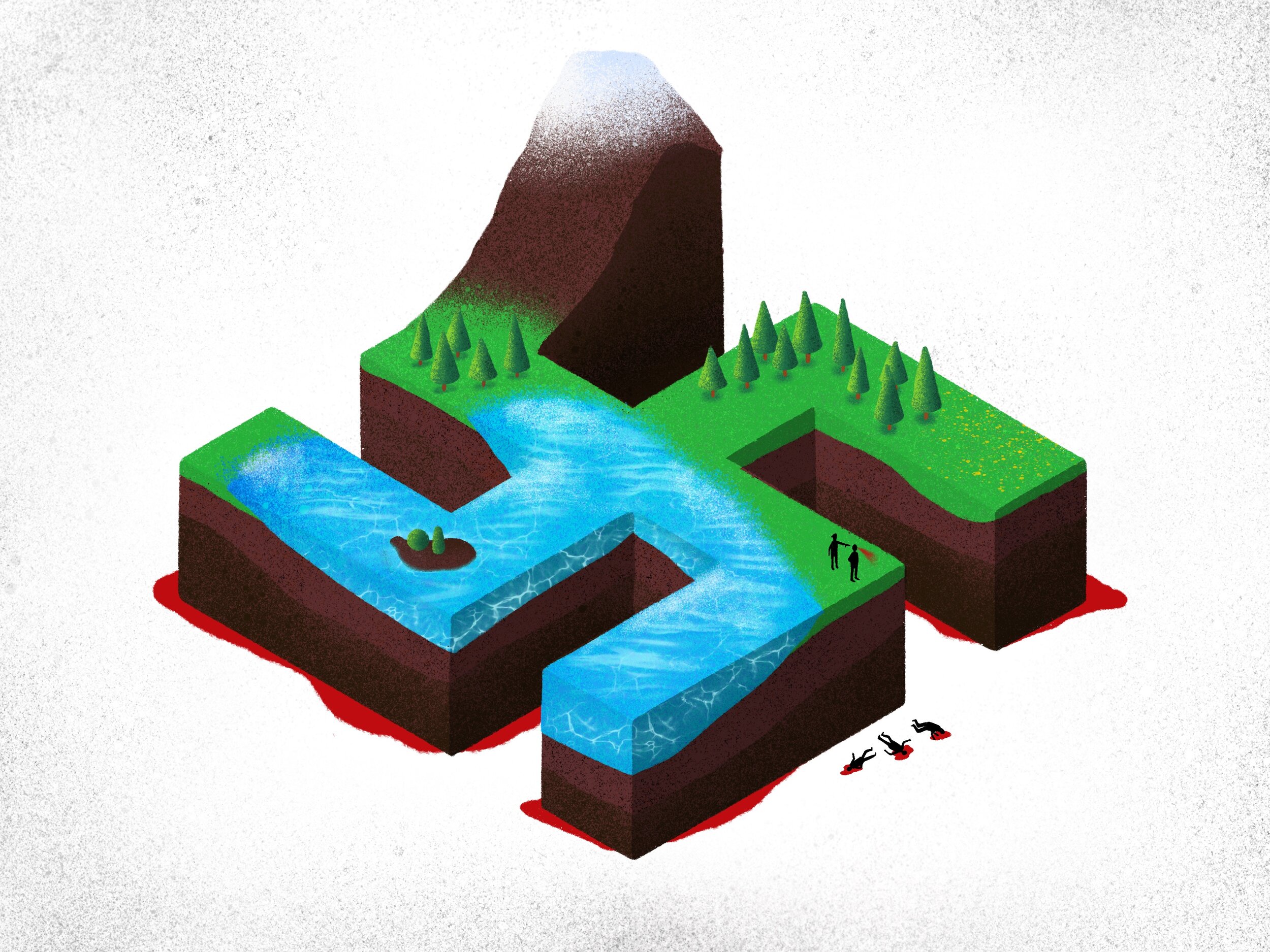

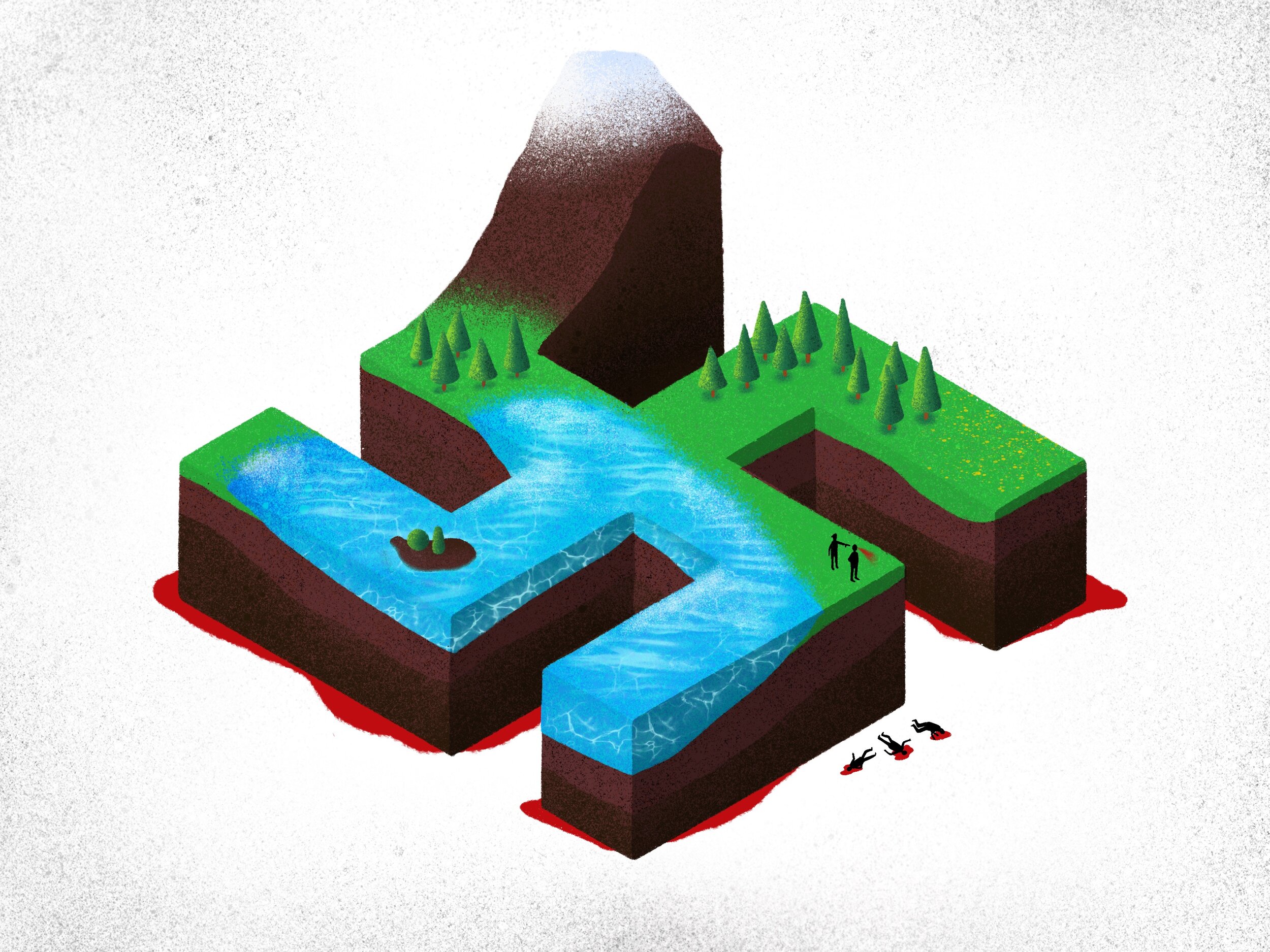

Humans are not the Virus: Why Ecofascism is Bad for You

Illustration: Nima Rahimiha

Our New Book Guide to Every City is now available from our online store!

From economic to environmental panic and finally the current pandemic, it seems like this century will be remembered as the age of global crises. Before panic over COVID-19 replaced panic over climate crisis as the primary threat to our existence, we have seen the rise of new forms of exposure-intensive activism from the likes of Greta Thunberg and UK based activist group Extinction Rebellion. As COVID-19 spread from Asia to the Western world, it has ceased being a talking point about Asian’s dirty habits into a global emergency - sorry non-western world, ¯\_(ツ)_/¯.

Nevertheless, the prominent catastrophic tone of recent climate activism, as well as the media, seems to be interpreting the virus as an environmental/moral problem, merely framing it as the result of human wrongdoing against nature.

The tendency to portray COVID-19 or global warming as a punishment, or an act of revenge from mother nature, has supported familiar far-right talking points. The Christchurch shooter who killed 52 people in June 2019 identified himself as an eco-fascist in his manifesto. Just two months later, Patrick Crusius who shot 22 people to death in El Paso, Texas; wrote his own manifesto, in homage to Christchurch. In this manifesto, he mentions the danger faced by the USA because of the environmental crisis and “consumption culture’’, revealing the eco-fascist motivations behind the horrendous attack. The evil muse to all this is Anders Breivik, the Norwegian extremist who murdered 69 young Labor Party members in 2011, whose manifesto also made references to humanity losing its pureness by the taint of inferior races.

This emerging movement might be posing a greater threat than imagined, since it’s ideological framework percolates into everyday discrimination and manifests as the moral policing of social life. Academic Betsy Hartmann defines eco-fascism as “the greening of hate,” a term which implies an effort to cover something ugly with something nicer, cleaner, prettier. This approach naively assumes that the green movement is fundamentally incompatible with the fascist movement, on the grounds that one of them is profoundly good and the other profoundly evil. This assumption is ripe to be challenged; because ideas of pureness and cleanliness have long been an important, in fact innate part of racist ideologies. The drive to preserve a pure environment is an essential part of the totalitarian fantasy. A fantasy in which land, race, air and even the bowels are expected to keep up with an impossible standard of “purity”. That’s why we have to problematise the idea of pureness/cleanliness first, so that we understand why these terms are darlings of the far-right and what political implications they make for racist ideologies.

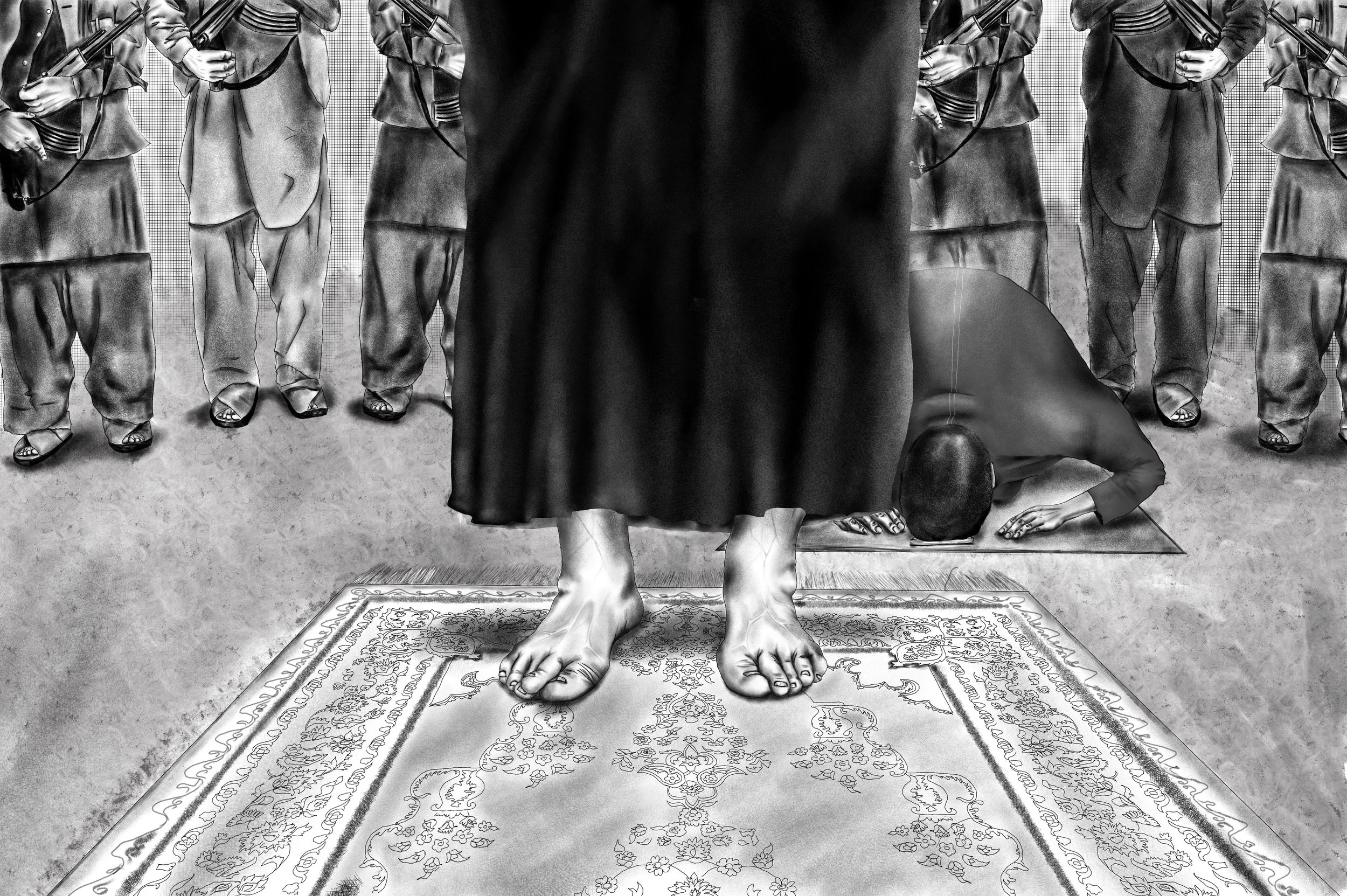

From the Hindu Caste system to the ideology of Hitler’s Third Reich; the fixation to keep the body and the environment clean and pure, has historically served an ugly purpose. The notion of “pureness’’, tends to imply the danger of something impure, contaminated, intoxicated and suggests a totalitarian understanding of bodies that need to be under perpetual surveillance to be disciplined, controlled and reduced in numbers. The idea that purity and cleanliness are inherently good, functions to underline class differences and ultimately racial discrimination. After all, we live in a society in which colours, food (just as I am writing this, the Turkish government declared a two day curfew. This caused widespread panic, many people ran to the markets in crowds. Some observers from the white-Turk twittersphere condemned panic buyers for buying snacks polite society considers unhealthy or redundant), body parts and even adjectives are hierarchically regulated and work in favor of certain living beings. In this hierarchy those who are fortunate enough to ratify their “humanity’’, come first. But this is an ill-defined category that can easily be misused to justify injustice. Slavery was rationalised through coding black people as the unveloved cousins of “humanity” (read: white European). A more recent manifestation of this long saga in Turkey, is Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s proclamation in October 2019, questioning Kurdish people’s right to a country by disputing the humanity of YPG supporters. The category of “humanity’’ is often mobilised with an internal hierarchy. Such arguments were put forth by the leading figures of the eugenics movements. One such figure, Ernst Haeckel, became an instant hit within the nascent Nazi movement by arguing that “lower” humans evolved from different species. The Nazi Party’s fixation on pureness reflected on many political regulations involving a strict strain of environmentalism under the motto “blood and soil’’ both of which needed to be kept uncontaminated (from other people, coming from other lands, their blood and their bodies). Fascism and environmentalism went hand in hand in many instances like this. Owning a land, owning a body, owning the right to things through land and body are all totalitarian fantasies that refuse mingling with others hence “getting dirty’’.

Eco-fascism historically relies on the idea that the environment can only be preserved if we spare it for a handful of people who really care about “mother nature”, overlooking the fact that nature is not pure in itself. Needless to say both the authors and the imagined beneficiaries of this utopian vision tend to be overwhelmingly white. This narrative has recently resurfaced with the spread of COVID-19, this time targeting Chinese people and blaming their dietary habits as the sole culprit for the global pandemic.

The doomsday narrative of climate activism can sometimes get lost in translation or be wilfully misread by those who see land as race- something that must be defended and preserved in a “pure and natural state’’. This fixation on pureness/cleanliness reaches beyond traditionalist politics which fetishise Norse mythology and return to the “virgin wheat fields” of the countryside. The notion of hygiene has long been a way to underline social status differences in urban life as well. The pressure on “individual change towards a cleaner and green future’’ also works in favor of class division through moral pressure in everyday life. Single usage plastic, especially bags and straws, may now be the most frowned upon thing in the world. In Istanbul for instance, everybody knows someone who is eager to preach bartenders about putting plastic straws in cocktails, or someone who complains about Arab tourists being “dirty’’.

Cleanliness is imagined as a moral imperative especially for city life, free from the effect/impact of education, class, gender, race and other major/minor drifts within the complicated strata of society and it’s not even always about climate change. Labeling people “uncivilized’’ just because they don't stand on the right side of the moving staircases of the subway or leaving garbage behind, is a popular and often unquestioned metropolitan etiquette, so is naming them “peasants’’, “dirty animals’’, “savages’’ etc. Judging other people’s competence in constantly upgrading their decorum is sadly very common. It’s fair to say this expectation shares important similarities with the eco-fascism movement. They go hand in hand with hubris, elitism and other forms of discrimination. People who don’t do the “right things’’ in this binary logic, should please leave the city, ultimately the country. Here in Istanbul it's the unwanted Syrian population and the “obnoxious’’ Arab tourists, people who are not “smart’’ enough to wash their hands regularly or buy the right kind of food to eat in quarantine, as well as immigrants from other parts of Turkey who can’t speak “proper” Turkish: mostly Kurds. We see the values that make a good human are accessible through certain capitals: racial, cultural and economic.

This narrative of division, or of deserving to live somewhere by assimilating, resonates in the direct correlation between climate change and overpopulation. This also reinforces the idea that a form of natural cleansing is the solution for environmental crisis. A process of “natural selection” in which species that cannot survive will naturally be wiped out. In this envisioned “distilled’’ future, the first ones to go out are of course the uncivilised non-human immigrants, black people, the poor and those who don’t have enough social capital to enable surviving the very conditions they are blamed for. But controls over means of survival are in a few hands and they are working to create a clean and pure future: a totalitarian utopia. This might be why many white supremacists and right-wing radicals are into catastrophic environmentalist narratives: A better nature for them means a whiter, (racially) cleansed future.

Eco-fascism suggests that the most practical way to protect life on earth for human beings is to reduce human population. Carbon footprints are measured, and unprivileged people are exposed as the most responsible. In this vision, a research studying the carbon footprint created by asthma patients’ plastic inhalers becomes conceivable. People who already carry the burden of racial/moral discrimination are once again blamed for not being moral enough and being too careless: Africans for Ebola, Chinese for Corona, homosexuals for AIDS. Protecting life means reserving it for certain people, people who come first, people who are worthy of it. People who are considered “human beings’’ enough. That’s why the discourse of population control harms disadvantaged groups first; immigrant, uneducated, poor and non-white people. Through declaring war and drone operations on other people’s homelands and not opening borders for them to flee war and oppression, through turning people into objects of negotiation and reducing them to pieces of paper, through not allowing them documents that would dress them up as “human beings”. All this cruelty is performed with the justification of protecting humanity from a vermin invasion. This dehumanising discourse is the first and most important step of setting up a eugenicist apparatus of population control.

In a world that relies on rationality, science and “practicality’’, total solutions may equate to annihilation. This may sound very rational to some, because it is so clean cut and scientific: The earth has restricted resources left, it is way overpopulated and it’s too late to turn it back. Someone will do the math: Reduce the population! As the El Paso shooter wrote in his manifesto: “The decimation of the environment is creating a massive burden for future generations. Corporations are heading the destruction of our environment by shamelessly overharvesting resources, If we can get rid of enough people, then our way of life can be more sustainable.’’ That’s why the apocalyptic narrative dominant in climate activism needs to be abolished. Because people can do some very interesting things in times of crisis, as the saying goes “extraordinary times need extraordinary measures’’ and in a post-holocaust world, people are alarmingly good at rationalising the inconceivable.

To bring about cultural and spatial change, climate activism must also challenge the mainstream narratives of consumption which ignores class, race and gender. We have to recognise that this fight is first and foremost political and we have to start targeting the leaders, the rich, the corporations and the state. Otherwise climate activism may very well stay as a movement in which people are divided in two, as right doers and wrong doers, this will only end up in misanthropy and resentment that eventually labels vulnerable people as “parasites’’. This is the state of mind which justifies mass deportations, wars and ultimately mass shootings and murders.

We can’t talk about climate change without talking about occupied lands, disability, displaced populations and gender equality. It’s a crisis yes, but it’s not transcendent. It’s important, yes; but not more important than any ongoing human rights struggle. It’s naive to assume that certain discourses would circumvent established connotations and reach transcending solutions; on the contrary, language has historicity and people interact on affective grounds. In the center of this world, stands whiteness with all its blinding “brightness’’ and this prevents everything, even climate change, from being a universal matter. Associated Press’s excisement of Ugandan activist Vanessa Nakate from an image (which featured Greta Thunberg with other young white activists) then defending the motive as being “purely on composition grounds’’ is just a small example of how whiteness still stands as an invisible threshold in every little action. We must never forget what historical connotations ideas like purity and cleanliness carry and how the collective unconsciousness remembers and interprets them. Over-reading is a must and the historical baggage of the environmentalist narrative cannot be challenged without being intersectional.