How Acupuncture Cured my Anthropology

Part I: The Fieldwork

I first stepped into late doctor Abut's acupuncture clinic at the wealthy Gayrettepe district of Istanbul in 2014. On the first day of what will be a two-year long fieldwork, I was excited about the prospect of 'discovering' previously unrecorded ancient networks of knowledge transmission which link China and Turkey. But as soon as I arrived, I realised that modern assumptions about identity and health are far more exciting than trying to reveal archaic connections between civilisations. As we were sitting in his clinic's waiting room, surrounded by patients, I told the doctor of my half-baked intention. He replied with what sounded like resentment: "The acupuncture I practice here, has nothing to do with China." He then recounted horror stories about how traditional acupuncture in China is practised by sterilising needles with saliva, or how Chinese physicians are almost purposefully inflicting pain on their patients. I tried to respond with contemporary fieldwork evidence about how acupuncture in China is conducted in sterilised, "modern" hospital environments. But it was to no avail.

For two years between 2014 and 2016, I became a regular at the doctor's office and had the opportunity to interview him at length several times. I have also discussed the doctor's medical approach with his two nurses, patients and his colleagues who often came to visit. In the summer of 2014, I had the unique opportunity to tag along with the doctor as he was organising the ICMART 16th World Congress in Istanbul. Lastly, I was given the privilege of access to the doctor's small archive of video interviews with patients and even conducted one of these interviews myself.

During my first few months in the clinic, Dr. Abut told me that he was practising "Turkish acupuncture". Initially, I thought the statement was an excessive display of nationalism. In time, I have come to appreciate the uniquely Turkish nature of his therapy. The doctor's therapeutic performance relied almost entirely on references around the social crisis which characterises contemporary Turkish identity. Dr. Abut identified his Turkish acupuncture as distinctly modern, and thus in opposition to local traditions like cinci hoca and üfürükçü hoca. Chinese medicine, by being associated with traditions of a "mystical" nature, also became suspect in his approach.

Dr. Abut's medical performance consisted of displaying his modernity and his command over biomedicine. One of the most powerful ways in which he conducted this performance was sending his patients to a laboratory to get tested for 3-methoxy 4-hydroxyphenylglycol. This chemical is indicative of the body's adrenaline production and it has been theorised in the 1960s that low levels of it could be indicative of depression. If my internet research is anything to go by, it appears to be frequently overlooked by most doctors, since a majority of them tend to associate depression with low serotonin. Doctor Abut explained his reasoning for the tests as follows:

Allergy to birch tree is formidable. If a doctor doesn't know what a birch tree is, how can we test for birch tree allergy? There are very few places that test for this... For example, should I say the formula? 3-methoxy 4-hydroxyphenylglycol. Let's say the patient has depression and they go to the doctor. Now does the patient have a noradrenaline related depression, or a dopamine-related depression, or a serotonin-related depression? Have you ever heard of a doctor who sends their patients to the lab to test this? I never have! So I called a lab over here and asked them: Why don't you test this? They said the doctors don't send their patients for this. But if you are a doctor, how can you prescribe medication to your patients without knowing if they are serotonin or noradrenaline related?

I have heard the doctor recite this formula to patients so frequently that I am convinced it constitutes a therapeutic ritual. In time, I became a part of his performance - as a young scholar who tails him, notepad in hand to record his medical approach for posterity. Every time I mentioned my own theory that acupuncture is a highly effective placebo therapy, he would recite the formula above to demonstrate that my knowledge of biomedicine is inadequate to make a qualified statement about his practice. I willingly played my part in these prompted monologues which gave the doctor an opportunity to put a young whippersnapper in his place in front of an admiring audience.

The patients were undoubtedly impressed by the doctor's habit of prescribing a test for a little known and arcane substance. One patient who was residing in Australia said she had not been able to find a laboratory there for such a test. This made her feel that a doctor from her own country was far ahead of his peers even in the developed Western world. As I will argue later in greater detail, the sense of restored trust in Turkey's ability to catch up with "the West" is a major element in the effectiveness of Abut's therapy. The doctor's sense of authority and his command over medical science is what made his treatment effective. From the frequency with which he prescribed the noradrenaline test, I believe that he himself suspected that many of the patients who came to him with a variety of physical discomforts were suffering from depression related ailments.

Besides tailing Dr. Abut, I have also ventured to find Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) practitioners with a contrasting approach. There are a handful of practitioners in Istanbul who cater to a radically different clientele. These tend to be diasporic Chinese or Uyghur Muslims who apply their practice from their homes. In contrast with Dr. Abut who relies on scientific symbolism for his medical performance, these practitioners draw from distinctly Muslim imagery. Consequently, their patients tend to come from a conservative background. These types of practitioners are harder to reach because they tend to only accept patients through common acquaintances. I was fortunate enough to conduct an interview with one such practitioner.

Ziyi was a Taiwanese national who married a Turkish man and converted to Islam. Ziyi's medical approach was almost diametrically opposed to that of Dr Abut. Unlike Abut, Ziyi practised a syncretic method which combined elements of Chinese medicine with an unorthodox Quranic exegesis. As we sat with Ziyi at a suburban Starbucks talking in a mixture of Chinese and Turkish she explained to me that she believes Allah gave her the power to detect and absorb the negative energy of others: "Allah believes in me and I believe in Allah." Much like Abut, the place Ziyi occupies within the traditional/modern spectrum is too complex to pin down.

Turkey is very different. Back home it's not like this. If you are called 'doctor' here, people believe whatever you say. Back home the doctor says something, but I will go see the traditional doctor (zhongyi). I will first ask the traditional doctor what to do. Only then will I think 'hmm maybe.' We can't just believe so easily. So I think it's a pity (yazık) for people here. You just take medicine. If a small child is hyperactive and won't stop. What will the doctor give? What will be their treatment? Drugs and cortisol. I think it's not right, such a shame. If there was a TCM doctor here, it would be really good, super.

Ziyi challenges the widespread assumption which makes modernity indispensable for the formation of a "critical faculty". After all, one of the fundamental tenets of modernity is the rejection of traditional authority figures like the clergy. Ziyi's concern about the authority of doctors reverses the modernist creed by questioning the contemporary power of experts. Ziyi and her husband were living in a newly built suburb, personally connected to a community of middle-class professionals and small business owners from a conservative upbringing. Such communities have started prospering with the election of the AKP government in 2002. Before this, conservative communities were systematically restricted from attaining professional careers, with legislative measures like banning women who wear the veil from accessing higher education.

The diametric opposition between the two practitioners goes beyond one of them being more 'modern' and the other more 'traditional' but also on where they locate their modernity and their tradition. As indicated earlier, for Dr Abut, modern scientific acupuncture is resoundingly Turkish. But although Islamic references form a crucial part of Ziyi's treatment, the geographic epicentre of her therapy is squarely located in China. This contrasts with popular perceptions which understand tradition as being insulated and modernity as being open to diversity. This diametric opposition gives an insight on the belief systems of these patients and the kinds of sociological reflections they find comforting.

Dr Abut's patients are staunch believer's in Turkey's modernising project, their reading of history emphasises how conservatives have persistently sabotaged these efforts by refusing to adapt their way of life. This reading is a classic among academic doyens in the fields of Turkish history and sociology like Şerif Mardin and İlber Ortaylı. For Dr. Abut's patients, being in the presence of a doctor who locates modernity within Turkey is a comforting experience in itself which facilitates the placebo effect administered during treatment. Ziyi's patients come from an ideology which believes that forced secularisation since the foundation of the republic has alienated Turkish people from their Islamic roots. They, in turn, find physical comfort in seeing the universal reach of Islam. Through figures like Ziyi, they confirm that being a global citizen does not depend on abandoning spirituality. Both of these groups suffer from a profound existential crisis. And to me, it feels obvious that an existential crisis of such magnitude can cause physical discomfort. But try explaining that to the review board of an anthropology journal.

“And to me, it feels obvious that an existential crisis of such magnitude can cause physical discomfort. But try explaining that to the review board of an anthropology journal. ”

Part II: Trials and tribulations of publishing

Unbeknownst to me at the time I was conducting this fieldwork, my PhD was rapidly approaching a brick wall. And with it, the legitimate right to call myself an anthropologist. I had to publish two articles in refereed journals as a graduation requirement and the first one wasn't doing so well. It was about the history of the fictional character Fu Manchu and the evolution of the yellow peril stereotype between the 1920s and the 1960s. I supplemented my reading of popular culture with fieldwork observations of white expatriates in Taiwan. I concluded the research by suggesting that a lot of the nasty Fu Manchu stereotypes are far from being dead and buried, but still very much alive in the everyday imagination of the white expat community in Taiwan.

Does my research sound interesting to you? Well, it didn't to the reviewer of the third journal I applied: "A depressingly familiar catalogue of offensive stereotypes", I believe they called it. Then there was the more historically minded reviewer from my fourteenth submission who wrote that my discussion of white beauty standards in relation to colonialism was irrelevant because Taiwan was colonised by the Japanese and not by Europeans. I was at a point in my life where I was questioning my place within the field of anthropology.

I don't want to be one of those people who lurk around academia and throw rocks at it. I have met people like that, they either remind me of Jordan Peterson or Slavoj Žižek. Bitter men who believe institutions who don't give them even more leg room to spread their ego are worthless. What I needed was a little more encouragement to explore my intuitions, to not have to hide that there is an emotional reason for why I care about what I study. If you are a young man from Ankara, your intuitions are too unfamiliar for the global custodians of academic credibility. You have to put significant effort into either translating or exotifying your emotions. The former wastes a lot of energy to coax the reader into acknowledging your humanity, the latter results in obscurantist treatises which deny the subaltern's ability to speak. And either way, you put all that effort into your work just so you can either be labelled modern/transparent/Western or exotic/obtuse/Eastern. It feels as though your existence lies dormant until the appearance of a Westernised audience to validate it.

When I walked into Dr. Abut's clinic I walked in as someone who was tired of being described as a mixture between East and West. It made me feel like my entire personality was a knot of headphone cables that I had to untangle and exhibit to gawkers: "These here are my Western bits, those over there are my Eastern bits." It is the experience of imagining my own personality as a knot that makes me suspect: There may be something about the inherited burdens of the Turkish identity crisis which causes physical discomfort. Two hundred years of wondering whether our culture was inferior because of it's comparative inefficiency in warfare. Hundred years of modernisation and secularisation by wiping out ethnic and religious minorities. And for me, almost two decades of trying to make my identity crisis legible so I can be taken seriously by the academic establishment.

“If I had felt my own confusion about identity as a knot in my stomach, somebody else could have felt it as a compression in their chest, another as an ache on their shoulder.”

My research about Abut’s clinic was received very much like my previous paper on Fu Manchu. Reviewers thought I was stretching when I claimed that the entire nation was undergoing a collective identity crisis. I imagine my suggestion that this crisis could be causing psychosomatic conditions, must have seemed even more contorted. Once these premises are rejected it becomes impossible to convince the reviewer that the therapeutic effect of doctor Abut's performance hinges closely on his ability to alleviate his patients' identity crisis. The reason I followed this chain of argument was of course deeply personal. If I had felt my own confusion about identity as a knot in my stomach, somebody else could have felt it as a compression in their chest, another as an ache on their shoulder. Academic language with its pretence to objectivity makes for a shoddy tool to paint an emotional landscape. Each attempt I made to try to be more 'objective' just made me feel like I was trying to impersonate somebody else's subjectivity. Impersonating somebody else's subjectivity means setting aside your own intuitions in favour of another's. Our instincts are at the deepest core of our personality, trying to replace them with someone else's requires a good deal of psychological self-mutilation. I am only just realising that I have been gnawing at my own roots just so I could get myself accepted.

It's not all doom and gloom. There are really encouraging academic works which explore the emotional structures of Turkish social and political life by researchers like Esra Özyürek and Nagehan Tokdoğan. Such works make it a little less difficult to describe how emotional structures can manifest themselves on the body politic. There are certainly plenty more researchers who work with different regions, who can successfully express well formulated analytical opinions without compromising from their emotional depth. But academic writing and its fixation on 'truth' makes it impossible to convey instincts without borrowing from an already established figure of authority. So each time I had to express an emotional state which allowed me to have a unique intuition I had to make it sound like some dead white dude had already come to the same conclusion. The necessity to qualify my emotions by references to Malinowski or Deleuze or Freud made me feel inadequate not just as an academic, but as a human being. Just as I felt orphaned by the academic community that rejected my intuitions, acupuncture is rejected by the medical establishment for being a placebo regardless of its actual effectiveness.

Part III: Hard truths and soft feelings

Anthropologists of my generation are weary from the overuse of binary categories that we study in introductory classes. For many of us, the obsessions of "founding fathers" like Levi-Strauss strike us as the products of an overconfident imagination which can only be sustained by white masculinity. His relentless belief that real human experiences can be made to fit into an elaborate Ptolemaic mechanism has driven him to contorted fantasies including the construction of outlandish "devices". Of all these great philosophers, Immanuel Kant has a special place for draping this binary over the world map and creating the East-West duality we are now familiar with. Kant believed that the sublime purity of reason had to be kept clear from contamination by the senses. He caricatured "Eastern voluptuaries" for enjoying sensual pleasures; massages to be specific. According to his logic, the Orient is classified as feminine and soft. The West, on the other hand, imagines itself as masculine and you guessed it: hard. It is difficult to ignore the strand of thought in white male philosophers to consider "softening" as a form of cultural infection which has spread from East to West. One of the best examples of this is Henry David Thoreau's tirade against what he perceives to be the privileging of "luxury" over "safety and convenience" in railcars: "[W]ith its divans, and ottomans, and sun-shades, and a hundred other oriental things, which we are taking west with us, invented for the ladies of the harem and the effeminate natives of the Celestial Empire."

Within these narratives of yellow peril and white diligence, the threat of Chinese domination is portrayed as the surrender of rock-hard white men to the velvety comforts of the Orient. This ideology enjoyed a massive revival in the 1950s as the vocabulary of the yellow peril passed the torch to the red scare. A dramatic example of this revival is journalist Edward Hunter’s 1958 testimony to the House Un-American Activities Committee. Hunter is known for coining the term ‘brainwashing’, to explain the lack of morale among US troops in Korea. He argues in his testimony that US troops were being kidnapped by the Chinese and taken to prison camps where they were "softened" through cognitive and physical torture and then indoctrinated to become communists. The pivot of Hunter's testimony is the assertion that communist brainwashing techniques have gone beyond the battlefield and they have been allowed to fester at the home front. According to Hunter, the alleged "softening up" of the American public is evident in domestic educational institutions which are eroding American individualism. This proclivity is instead being replaced by a conformist tendency which prioritises "getting along" over saying "what's right is right". Hunter's narrative forms the backbone of the 1962 movie, The Manchurian Candidate. The opening scene from the movie illustrates the "softening" of American POWs into docile servants of international communism.

Brainwashing scene from The Manchurian Candidate

Scientific establishments and universities are at the forefront of creating the defences that protect Western civilisation from cultural invaders. This tendency manifests itself in narratives of infiltration and 'political correctness' that are being constructed around Confucius Institutes. Confucius Institutes are language teaching institutions that are established within foreign universities with the support of the Chinese government. These institutions are legitimately criticised for their censorship of issues regarding human rights abuses in the People's Republic of China. There is also a more militant school of thought which considers the institutes as the spearhead of an assault on "Western values". Renowned anthropologist Marshall Sahlins has written a harrowing booklet arguing that the language teaching institution is a Chinese propaganda tool which disguises itself with a "benign description" and the "semblance of academic legitimacy". Sahlins expresses concern about how these Institutes woo Western universities by providing high-quality services to students and covering their own costs while doing so. This line of argument builds on Edward Hunter's legend of American G.Is who are 'brainwashed' by mischievous Asian specialists and his fears of infiltration by feminised, communist, anti-American elements. Objections of this nature place freedom of Speech in Western countries at the centre of concern, instead of the direct victims of the Chinese state's violence. Such is the veneration of 'truth' as a core element of whiteness that it eclipses concerns about real and immediate suffering. And this is why acupuncture is so vehemently rejected by large sections of the biomedical establishment.

The 2002 World Health Organisation (WHO) report on acupuncture is something of a Rorschach test for how passionately someone detests acupuncture. This report argues that even if it were true that acupuncture functions as a placebo, "this can hardly be taken as evidence negating the effectiveness of acupuncture". Critics believe that the report is biased because of WHO's prioritisation of "political correctness above truth". A widely cited peer-reviewed article titled Acupuncture is Theatrical Placebo, for instance concludes by portraying acupuncture patients as mindless fashion slaves: "No doubt acupuncture will continue to exist on the 'High Streets' where they can be tolerated as a voluntary self-imposed tax on the gullible". The implication that acupuncture is a High Street fashion craze, re-emphasises the suggestion that it is a phoney practice based on crackpot passions rather than sound reasoning and science. These authors genuinely believe that the heart of the Western world is caught up in a tug of war: Cold, hard, logical scientists on one side and hare-brained irresponsible snowflakes on the other.

“This reasoning chastises placebos not because of their therapeutic failure, but because their effectiveness threatens to obscure devoted service to an idealised notion of ‘true’ diagnosis.”

WHO's acknowledgement of acupuncture worries strident critics, because it signals that a reliable international institution has been brainwashed by an ideology which values feelings and fashion over facts. The modern therapeutic regime is founded on denying the cultural variability of pain. This approach rejects the study of how emotions can affect the wellbeing of individuals and societies. Wholistic systems like Chinese medicine which rely on the compatibility of metaphors between patients and physicians are rejected for obstructing the 'proper' application of medicine, which has to be universal. The introduction of ritualistic elements and metaphors which assist patients to make sense of their condition are turned down on the grounds that they are not universally repeatable. The loudest objections to placebos have no evidence to argue that it is an ineffective form of treatment. On the contrary, they acknowledge that the effect of placebos are so "powerful" that it becomes a "highly misleading factor when it comes to assessing the true efficacy of a treatment". This reasoning chastises placebos not because of their therapeutic failure, but because their effectiveness threatens to obscure devoted service to an idealised notion of 'true' diagnosis. The prioritisation of revealing the 'truth' over patient welfare translates into a culture of emotional detachment among medical personnel. This regime of enforced objectivity results in profoundly biased decisions which systematically dismisses the suffering women and people of colour.

My conflict with academic authorities mirrors the rejection of acupuncture and it's practitioners like Ziyi and Dr. Abut. When placed against the cold, hard, objective truths of authorised science, we come across as effete orientals who want to talk about feelings, intuition and community; while real scientists are solving real problems. It's just a hunch, but I think I know why our approaches are met with such screeching resistance by the predominantly white stewards of the scientific community. It is because in order to truly wrap their minds around our intuitions they will have to give something from themselves. Just as I was worried about losing my own instincts and my sense of self while trying to translate my emotions. They are frightened about eroding their own roots by cross-pollinating with our feelings and instincts. The way societies respond to placebos reveals something profoundly intimate about who they are. A society which is triggered by the idea of placebos displays symptoms of a collective yearning to be cocooned by ice cold walls fact. Of course, the irony is that the zealous defence of a 'universal' and 'rational' health system, uncontaminated by emotions and intuitions is in itself a deeply emotional reaction. But the feelings involved in this zealotry are kept well outside of public scrutiny. I am interested in dissecting the collective emotions that lie beneath the parade of indifference which marches across the main arteries of 'scientific reason.' My own intuition is guiding my scalpel to the historic moment where colonial history intersects with the development of medical science.

Part IV: The roots of a fear

Western fears of being infiltrated and brainwashed by an alien medical system are ironic, considering how medical institutions have been crucial to the entrance of colonial powers into China. The strategy of infiltration was an openly stated goal of protestant missionary organisations. One US missionary, W.A.P Martin has even written instructions for using medical care as a means for converting the Chinese to Christianity. The title of his 1897 essay is self-explanatory: Western Science as Auxiliary to the Spread of the Gospel. Hospitals were seen by missionaries not just as "environments in which doctors could practice medicine; more fundamental was their role as institutions in which patients could learn to become healthy citizens and good Christian ones at that". This mission was then passed on to secular institutions also. When in 1915 the Rockefeller foundation purchased the Union Medical College from the London Missionary Society, they agreed to cooperate with Protestant missionaries to "be a distinctive contribution to missionary endeavour". The Rockefeller foundation's 1917 annual report outlines how the architecture of the building will be "in harmony with the best traditions of Chinese architecture, and will thus symbolise a desire to make the college not something imposed from without, but an agency which shall in time become an intimate, organic part of a developing Chinese civilisation."

Lam Qua’s painting of Wang Ke-King

As the Rockefeller Foundation used architecture to convey new subjectivities, representational art has also been used to facilitate converting Chinese bodies into medical patients and Chinese souls into Christianity. Ari Larissa Heinrich's study of medical portraits painted by Lam Qua between 1836 and 1855, illustrates this point very clearly. These portraits were commissioned by the American medical missionary Peter Parker, to advertise his medical practice to potential patients in China and funders of his enterprise in Europe and the US. The portrait of patient Wang Ke-king who died from his tumour after his wives and mother refused Parker's intervention is a good example. Both Parker and Lam Qua emphasise that Wang had died not from the tumour but from the backwardness of Chinese culture. In Lam Qua's painting, Wang is depicted from behind with his back turned and his long queue braid hanging down to his ankles, over the giant tumour which extends from his waist to just below his knees. Heinrich notes the symbolic importance of this imagery: "[T]he queue serves as the literal yardstick against which we measure not only the astounding dimensions of the tumour, but (we are meant to read) the extraordinary backwardness of a culture that would not allow Parker to operate on it". Christian missionaries like Parker and secular institutions like Rockefeller appear to have made concentrated efforts to "soften up" the Chinese public into accepting not just medicine, but also a collective sense of inferiority. Meanwhile, a substantial part of the acupuncture community in the West maintains discourses of Chinese inferiority and claims to have "reinvented" or "rediscovered" something called “scientific acupuncture.”

I have witnessed the debate between 'scientific' and 'traditional' acupuncture emerge as a fault line at the ICMART Congress of 2014. During the congress, Dr. Abut led a group of Turkish physicians who firmly sided with modernisation. During our conversations following the presentations, I have also witnessed him express discontent about physicians who made presentations that focus on the spiritual aspect of TCM. Dr. Abut was introduced to acupuncture during the 1970s while he was working in Germany as a surgeon. He was personal friends with a circle of European physicians who were working to find connections between acupuncture and neurobiology. One of these physicians, Johannes Bischko was such a close friend that Dr. Abut commissioned a sculptor to make his bust. The bust was on display right at the entrance of the clinic. Greeting cards from Bischko also adorned the walls of the doctor's waiting room.

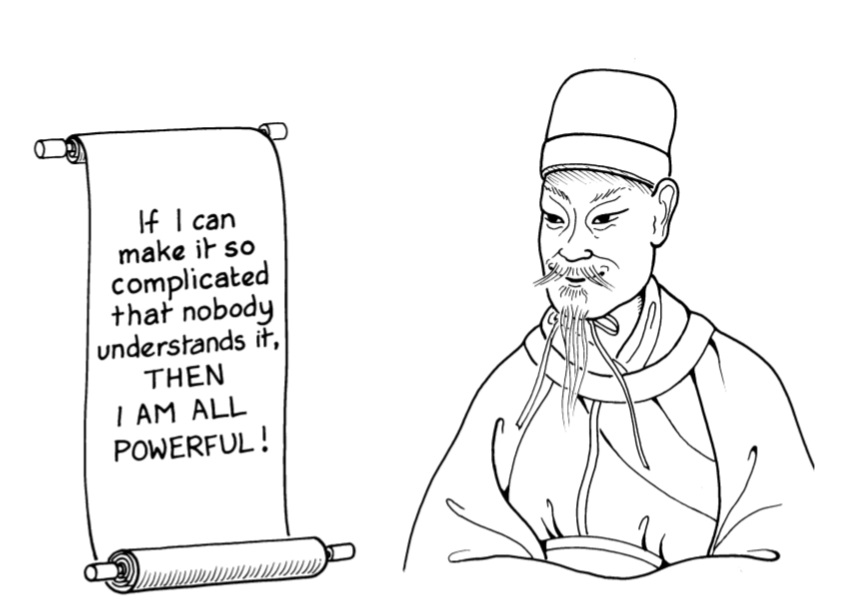

Another figure associated with this circle of physicians is Felix Mann, whose textbook Reinventing Acupuncture is something of a manifesto for the scientific approach. Mann rejects some of the key principles of traditional acupuncture like meridians. Instead, he advocates a revised acupuncture that is purged from inscrutable philosophical metaphors and relies on the common sense and experience of the physician. Mann is adamant that ancient Chinese scholars were motivated by the desire to monopolise the practice of acupuncture, they have needlessly complicated everything just to make it "worthy of a scholarly intellect". To this end: "They added yin and yang, the five elements and other ideas of Taoist natural philosophy". Mann's text is even accompanied by an illustrated Ancient Chinese scholar who declares: "If I can make it so complicated that nobody understands it, THEN I AM ALL POWERFUL" with an expression of smug serenity on his face.

Mann insists that he and he alone is the pioneer of a revolutionary new approach: "No experts told me of hearing something similar; nor for that matter could I find much of a similar nature in acupuncture and related literature". Nevertheless, according to anthropologist and acupuncture historian Volker Scheid Japanese acupuncturists had made the same criticism against traditional acupuncture as early as 17th century by rejecting "all theorising in favour of a strictly phenomenological approach to clinical practice [...] Their goal was to progress directly from the observation of symptoms and signs to prescriptions, without resorting to intellectual hypotheses regarding the pathology of the qi dynamic". Following the well-established tradition of white men who claim to have reinvented anything, it turns out that Mann simply hadn't done his homework.

The alleged reliance of acupuncture to metaphors like the five elements or analogies between meridian flows and the Grand Canal are seen as unscientific by modernisers who follow Mann. Western commentators have pointed out that the Confucian taboo against dissection is responsible for Chinese medicine's reliance on fanciful philosophical theories. As early as 1774, Francois Dujardin mocked Chinese medicine for being "no more than a shapeless mass of systems, of tentative efforts, of conjectures". The inclination of TCM to favour a philosophical approach rather than an empirical one is seen as irreconcilable with the values of the Western Enlightenment. But offering a narrative about the causes of disease that patients can relate to, contribute significantly to their health. Even modernisers make use of narratives, Mann builds a cult of personality dedicated to prioritising the experience of the physician over all else. Dr. Abut, who exuded a comparable sense of confidence, supplemented his approach with other narratives about manipulating electric currents which run through the body by using silver and gold needles. One of his frequently used metaphors was comparing the patient's body to a computer and claiming he will install new software to make it better. Ziyi, on the other hand, had a syncretic approach which professed that diseases were caused by djinns. She claimed she would induce a hypnotic state on the patients and confront the djinns personally. The question of which kind of acupuncture therapy works is inseparable from the question of what kind of stories a society tells about itself. And this is why acupuncture is so profoundly intimate and frightening to some.

“ The expectations we have when we walk through the doors of a hospital, the feelings we get when we take off our clothes for examination or when we enter an MRI machine are shaped by our sense of self. Our sense of self, in turn, has a profound impact on our wellbeing.”

Of course, I am not denying the effectiveness of biomedicine, nor am I claiming that explaining patients their condition is a superior form of treatment. I am suggesting that the taboo around expressing and understanding intangible human emotions can be impeding developments in medicine just as much as the taboos around dissection. Medicine is more complicated than just following universally applicable procedures. The expectations we have when we walk through the doors of a hospital, the feelings we get when we take off our clothes for examination or when we enter an MRI machine are shaped by our sense of self. Our sense of self, in turn, has a profound impact on our wellbeing. The ways in which the human body is covered with fabric, projected in artistic representation or placed within a built environment determine how it will react to various kinds of treatment. The relentless objection to Chinese medicine is not because it is ineffective as a cure. It is the manifestation of the fear that the most intimate signifiers which provide psychological and physical comfort are under threat of degeneration due to Chinese infiltration. These signifiers are tightly wound in with an individual's sense of self and where they locate themselves in the world. If you are located in Turkey, these symbols and signifiers gain a very unique meaning.

Part V: Healing the Turkish body politic

Metaphors of politics and health flow in both directions. During the modernisation of Turkey in the 1920s, it became common to associate dissident elements with disease and infection. This theme is central in the assessment of the Dersim region, where an uprising by the Kurdish Alevi minority was brutally put down in 1938. A 1926 report written by Cemal Bey, the mayor of Diyarbakır, assesses the situation in the region with such diagnostic terms: "Dersim is a dangerous abscess for Turkey, which is created by ignorance, internal and external encouragement, poverty and Kurdish inclinations. This abscess has to undergo a decisive operation. To this end, it is necessary to first stockpile weapons and then carry out reforms". The construction of hospitals was naturally at the forefront of suggested reforms, to establish the legitimacy of the Turkish state. Repression followed by the provision of services is portrayed as a curative and preventative treatment for the region. Advancement of medical services carried a particularly important role. A later official report from 1933-1934 reminds that "ruling over people's hearts and spirits through health is the shortest and most precious way".

The battle between modernity and tradition occupies a crucial part in the lives of Turkish citizens. I can't imagine what residents of Dersim must have felt when they saw representations of their bodies as viruses that must be decapitated. But I am familiar with today's Turkey and being exposed to a stream of discourse which treats me and my friends like we are parasitic aberrations. Christopher Dole discusses the centrality of these tensions in his ethnographic study of faith healing in Ankara. A significant amount of Dole's ethnography revolves around the figure of Zöhre Ana, who combines theological signifiers from Alevi religion with the staunch secular ideology of Kemalism. Zöhre Ana places both herself and the founder of the Turkish Republic, Atatürk within the same saintly genealogy and even claims to channel his voice in her poetry.

Like Dr. Abut and Ziyi, Zöhre Ana is impossible to pin down within the modern - traditional dichotomy. Each one of these healers draw from deep wells of symbolism which make superficial distinctions between modernity and tradition obsolete. Zöhre Ana's headquarters are at the Mamak district of Ankara. The building is referred to as a dergâh (dervish convent). Dole reports that the plans came to Zöhre Ana in a series of visions. The dergah is partitioned into two parts, with the main part dedicated to all the daily functions like receiving patients, administration and even a gift shop. There is also a small subterranean section of the building which is fashioned to resemble the interior of a cave which serves as a museum of sorts containing antique items and even a lion-shaped spigot dispensing sacred water (zemzem).

I have observed a similar dualistic symbolism at Dr. Abut's clinic. Although smaller in comparison to Zöhre Ana's dergâh, Dr. Abut's clinic is composed of two wings. On one end is the waiting room where the Doctor spent most of his time socialising with the patients. On the other side, is a consultation room which patients only enter during their first visit. The long corridor which stretches between the two wings leads to three sick rooms with a total capacity of six beds and the yıldızlı oda ("starry room" named after the small dome above it, adorned with star motifs), which houses a laser device. I am told the laser from this device functions as an acupuncture needle. The name of the room rings as a reference to the Yıldız Palace built by Abdulhamid II in 1886. The architectural reference to domes is also subject of great controversy in Turkey. During the 70s, the project of Kocatepe Mosque in Ankara was scrapped and demolished by conservative administrators on the grounds that it was "too modern". One of the principal reasons for the decision was that the mosque did not have a dome. The subject of domes continues to be a divisive issue among left-leaning and conservative architects to this day. This debate spills over to the general public on occasions. One of the key occasions was surrounding the imprisonment of Tayyip Erdoğan in 1999 for reading a poem which stated: Minarets are our bayonets, domes are our helmets/ Mosques are our barracks, the faithful our soldiers.

“For a lot of Turkish people who are experiencing a permanent state of political crisis reflected over architectural forms, seeing a laser acupuncture device under a starry dome alone can be conceived as a therapeutic act. ”

All this debate about a simple architectural form should give an idea about how combining a starry dome and a laser device is the material embodiment of the tension between modernity and tradition in Turkey. For a lot of Turkish people who are experiencing a permanent state of political crisis reflected over architectural forms, seeing a laser acupuncture device under a starry dome alone can be conceived as a therapeutic act. This simple material placement temporarily resolves a fundamental identity crisis by reconciling the old and the new under a consistent aesthetic. Many who enter the clinic, including myself see our inner conflicts materialised in this room. So much has been made about how East and West will never meet or how tradition and modernity are worlds apart, that our own existence appears as a cosmic paradox. Yet none of us makes a conscious effort to combine anything, we are just simply existing like a laser device under a starry dome.

This harmonisation is also emphasised through the contrast between the consultation and the waiting room. In terms of their utility, these rooms mirror the public/private separation of domestic spaces. The public sphere of the waiting room represents a distinctly 'modern' identity whilst the more private consultation room presents a 'traditional' aesthetic. The waiting room was essentially indistinguishable from any other private clinic or hospital in Istanbul with white walls and floor tiles and a coffee table at the centre with magazines. Dr. Abut was frequently engaged in conversation with his patients on a wide range of topics, while a small video screen showed home videos filmed during the doctor’s many voyages. These screens were also placed in the sickrooms for resting patients. The consultation room, in contrast, exhibits a far more sombre aesthetic. This is the room patients first enter when they visit the doctor and discuss their ailments. The only media in display here are shelves stacked with books and two canvas paintings; one of Abut's father Ali Rıza Abut, and one of his grandfather Mehmed Fuat Efendi. Ali Rıza stood behind his son's desk and Mehmed Fuad was on the adjoining wall. Two large tuft leather chairs diagonally faced the doctor's desk. The walls were darkened by an imposing wood panelling, lighting was dim and the prevailing colour was brown. There were also old fashioned emeralite lamps (the classic banker’s lamp) both by the couch and the office desk, giving the place the feeling of a Victorian library.

The references to the 19th century and Abdulhamid II in the interior architecture are not arbitrary. This is the period in which Dr. Abut's grandfather, a rich merchant from Damascus had moved to Istanbul. Mehmed Fuat Efendi is remembered today for the properties he once owned in Istanbul, one of these has even become an international tourist destination after housing popular Turkish soap operas. His son Ali Rıza refused taking over his father's business and studied in Europe to become a doctor, he has subsequently become an influential physician in Turkey's early Republican era. Dr. Abut occasionally discussed this family history with his patients and has written a column for an online publication citing his father's charity works and his participation in the Republican revolution in the 1920s. Abut claims in this article that his father was offered a position as the fledgeling Republic's first minister of health by Atatürk himself. Dr. Abut's pedigree contributed to his sense of authority, not just in the medical field but also in subjects varying from art and literature to contemporary politics. Patients felt privileged to be in the doctor's company and listen to him.

The therapeutic effect of the doctor's company was frequently brought up by the patients. One patient teasingly asked, "are these discussions included in the bill?" Conversations often revolved around but were not restricted to the subject of acupuncture and medicine. Patients have often expressed that after their ordeals with biomedical medicine, their consultation with Dr. Abut was the first time they were given a thorough explanation of their condition. Their sense of awe for the doctor's medical skill was often expressed in terms of its incomprehensibility to laypeople. One patient who cancelled a scheduled surgical operation at a hospital to seek the doctor interrupted himself while attempting to summarise Abut's theory of acupuncture:

Of course, I can't speak here with scientific data. I don't have that kind of competence. To say this you have to be a scientist. You have to at least know pharmacology. You have to know how deep to pierce which needle to release a certain kind of medicine.

In the eyes of his admirers, Abut's unattainable level of authority reached beyond the field of medicine. One patient who had undergone multiple surgical operations for hypoglycaemia related pain expressed his admiration for the doctor's wisdom in fields that are unrelated to medicine. After a lengthy discussion about how he had been treated with haughty indifference by doctors in his previous hospital visits, he explained why he found Abut's approach to be so refreshing:

I observed that instead of a patient-doctor relationship he [Dr. Abut] addresses to you as a friend and establishes trust. I mean you don't just talk about acupuncture. You talk about literature, you talk about art, you talk about his voyages, you talk about life. And you see that this is an astounding therapy. Mehmet Hoca is one of the few experts in his field in the world. But beyond this, more importantly... assessing his expertise is beyond me. But his humanistic side and his doctor-patient relationship are exemplary.

The same patient also suggested that the doctor is an evliya (wali), the title for Islamic saint, translated as "friend of God." Dole notes, in his study that Zöhre Ana claims herself to be an evliya for her miraculous healing powers. This patient, however, emphasised Abut's worldliness, not through supernatural powers, but by comparing him specifically with Evliya Çelebi, a renowned explorer and travel writer. This attribution was due to Abut's screening of his home videos in the clinic and the friendly atmosphere that he encouraged among the patients:

I called him Evliya Çelebi. He reveals another therapy by showing videos of his travels in the waiting room. Not just the therapy, but also his speech. The videos and stories of his travels. I have followed how people watch these videos. You are in a physician's waiting room but there is no tense feeling. Normally in waiting rooms, you will have sulking people having forced conversations with their limited knowledge about their conditions. Here, people whose ailments I know are having a cosy chat while waiting for treatment. [...] Relationship with the physician is not a regular patient-doctor relationship, it's more like having tea with a friend. He not only shares his scientific explanations about the world but also his experiences. [...] Physicians and patients have different expectations. The physician will do his work, whilst I try to get better. While I try to get better, the physicians could choose to only do their job. But if they can show some human kindness, this is fifty per cent of the therapy. Mehmet Hoca gave far more than that.

Patients who had no prior familiarity with acupuncture almost entirely disregarded its ancient Chinese origin, and instead described it as one of the absolute necessities of modern life. Many such patients lamented that this practice has not spread wide enough in Turkey and attributed it to Turkey's backwardness. One patient blamed the conservative AK Party administration for "keeping Turkey in the dark ages" by negating acupuncture. Other patients who had prior familiarity with acupuncture from their experiences abroad, insisted that Abut's method was superior to Chinese and Japanese methods, because of its scientific nature. Most of these patients agreed that Abut's diagnosis and treatment "made sense."

It is hard to tell if the reasonableness of Abut's diagnosis is caused by his sense of authority or vice versa. What is clear however is that patients described themselves as "surrendering" to his expertise. The importance of conveying a narrative to the patient about their condition, of making them feel relaxed and actively involved in their own treatment and resolving deeper social conflicts within them should not be dismissed when assessing the impact of Chinese medicine as a form of therapy. One patient has summarised his confidence in acupuncture along these terms by insisting: "Whoever claims they have not benefited from acupuncture have either not surrendered to the doctor entirely or they don't believe in the treatment."