Nightmare on Togo Street: Traveling to Istanbul Through the Magical Portal of Japanese Nationalism

Illustration: Aude Nasr

Mangal Media is supported entirely by readers like you! Please visit our Patreon page to browse our pledge options and rewards.

There is a myth in Japan. In 1905, Japan defeated Russia and became the first non-European country to beat "Christian Europe". Non-European people all over the world and any nation with enmities against Russia were elated. In Finland, they named a beer after Togo, the famous admiral who defeated the Russian Baltic Fleet. And in the Ottoman Empire, a street was named Togo in his honour. I saw this myth more than 15 years ago when I was both young and stupid enough to believe it. One day, I asked a Finnish guy I met online about Togo beer. His answer was: "I have no idea."

He then insisted I give him my address so he could send me Togo beer. He later escalated to ask for pictures of my face and certain body parts, using obscenities that a teenager living in a non-English speaking country had never heard. Thus, a 15-year-old Japanese boy failed to confirm the existence of Togo beer, but learned another important lesson: the internet is a dark place.

It was almost impossible to review these urban legends. Prof. Akira Asano, a scholar of engineering who has lived in Finland, investigated the existence of Togo beer and reached the conclusion that it does not exist. It was just a variant of the local beer label Amiraali, with the face of world-famous naval admirals, including Zinovy Petrovich Rozhestvensky, the admiral of the Russian Baltic Fleet, printed on the cans. He found that Amiraali was discontinued when its parent company Pyynikki went bankrupt in 1992. Asano concludes that Amiraali with Togo's label doesn't glorify Japan's victory in the Russo-Japanese War. This rumour was only a product of nationalistic Japanese people's imagination. But that’s not where the story ends! A Japanese beer company bought the copyright of Amiraali's Togo label and started producing and selling it as Togo beer. An urban legend has thus incarnated in Japan as real Togo beer. This may look like a lame joke, but there's a nationalist context to this story, as I will explain later.

Now, what about Togo Street, which is said to exist in Istanbul? I have never heard of it. Neither have any of my Turkish friends. However, Togo Street has been mentioned again and again in recent years since Internet communication fanned the flames of misinformation. Despite this, no one has indicated its exact location. On the other hand, it is also true that no one has empirically refuted the existence of Togo Street. Unlike Togo Beer, it takes more than Turkish language skills to investigate the myriad streets of Istanbul that change their names over time. Since Japanese Ottomanists do not care to engage in this kind of silly gossip, there has been no fact-checking of Togo Street. This mythic street has turned into an Internet Schrödinger's cat. We have to open a box with many gimmicks to confirm its existence.

“This mythic street has turned into an Internet Schrödinger’s cat. We have to open a box with many gimmicks to confirm its existence.”

First, I would like to look at the narrative of Togo Street as it is told in Japan. The oldest tweet mentioning Togo Street is from 2009. This is a quote from a book titled Japanese History Surprisingly Only The Japanese Don't Know by an essayist named Reiko Durand. The subsequent tweets referring to Togo Street were also mostly written in the form of hearsay, lacking confirmation of actual visits to Togo Street in Istanbul. Some cite books like the one mentioned above, suggesting that the origin of this rumour can be traced to printed media.

Google Books search reveals references to Togo Street in various media, ranging from general readers to magazines and articles. One of the most representative examples is the international politics and Islamic studies scholar Yoshiaki Sasaki's For the Next 50 Years; the World Will Revolve Around Turkey: Seven reasons for Turkey's great leap forward. Sasaki is famous for getting arrested after stabbing his student with a katana in his office at Takushoku University. He has also claimed during the subsequent police interrogation: “I wanted to teach him how deadly going to the Middle East is.” In this book, Sasaki makes the following claims:

1- A street in Istanbul was named Togo Street.

2- Some parents named their children born around this time Togo.

3- General Maresuke Nogi, who captured the impregnable fortress of Lüshun Port during the Russo-Japanese War, was also known in Turkey. Some parents gave their children the name Nogi.

Almost verbatim forms of textual plagiarism can be found in numerous books. In any case, the two points are stated repeatedly as if they were copied and pasted: 1) the Ottomans named a street in Istanbul Togo in honour of Japan's victory in the Russo-Japanese War, and 2) many parents named their children Togo and Nogi.

Many of these discourses appear in books that unfoundedly praise Japan, and many of the authors are prominent right-wing intellectuals. It is worth noting that they include Yoshiaki Sasaki mentioned above and Osamu Miyata, a contemporary Iran scholar. It is surprising to see those Middle East experts making references to Togo Street without any evidence. The same packaging of these two discourses can be seen in a 2003 article titled One Hundred Years of the Russo-Japanese War: The Yellow Peril Theory and the Comintern's Perspective by Yoichi Hirama, a former assistant admiral of the Maritime Self Defense Force, published in the otherwise respectable peer-reviewed journal History of Political Economy. This article is also reproduced on Hirama’s personal website. The exact same sentences from this article can be found in another article in 2008, titled Two Books That Changed the World: Inazo Nitobe's Bushido and Chūon Sakurai's Human Bullet in Ryotaro and the Russo-Japanese War. In the latter, Turkey is mentioned along with Iran as examples of “Arab countries”...

The Turkish case is also written in a hearsay style without any references, like in Sasaki and Miyata's books. We have another example of this plagiarism in a 2004 article, Turkey and the Russo-Japanese War: An aspect of the international conflict published in the Journal of Law, Politics, and Sociology, a bulletin at Keio University. The author is Masaru Ikei, a far eastern international politics historian and an emeritus professor of Keio University. I don’t touch on any more than Togo here, although I have many words to say about his article. The development of the argument is very similar to Hirama's articles. Both refer to Mikado-nameh, a Persian chronicle in praise of the Japanese emperor, before mentioning Togo street and children named Togo. Ikei writes that the author is Mehmet Akif, a famous Turkish poet, while Mikado-nameh is written by an Iranian poet, Hossein Ali Tajer Shirazi. I cannot tell why he confuses this essential point, but at least he has the conscience to state his sources, compared to his plagiarist friends. According to his reference, the combination of Togo street and children named Togo and Nogi comes from a 1995 book by former ambassador of Japan to Ankara, Yoichi Yamaguchi: Turkey Comes into View: The importance of this pro-Japan country. We can conclude that Yamaguchi's book is the first source that combines the claims listed above. Yamaguchi’s book also introduces a new puzzle piece, in the shape of the Turkish shoe manufacturer and retailer TOGO. This added snippet gives a certain tangibility to the discourse which is later strengthened by a plagiaristic echo chamber.

Let’s start with the claim of Turkish children named Togo. I can confidently say I have never met nor heard of anyone. Many of these sources acknowledge that it is not common today, but no one provides an actual example. Even when some claim they met an elderly man named Togo in Turkey, they don't even take a picture of that man. The only firm example referred to repeatedly is Halide Edip Adıvar, a writer who named her son Hasan Hikmetullah Togo in the 1930s. However, according to her memoir House with Wisteria, Togo was just a nickname. Although it seems true that many boys were called Togo as a nickname at that time, claiming that many children were named Togo or Nogi is hyperbolic. Hasan Hikumetullah's nickname has likely avalanched through a game of Chinese whispers into an unstoppable urban myth. Adding Nogi here is most likely the ultimate result of this game. Sasaki makes the cringe-worthy statement: "Whether ‘Togo’ or ‘Nogi,’ the name must have been associated with the wish that the child would be raised to be strong?"... Oh, no.

In addition to this story, there is one more example they see as proof of the existence of Turkish children named Togo. It is Turkish shoe manufacturer TOGO. Yes, the store is called Togo, but is it really our Togo? Let's see where this name comes from. According to the description of its short video explaining its history on YouTube, TOGO was founded as a leather shop in Beyoğlu in 1937, and its name comes from the founder Togo Acemyan. He must be an Armenian. As far as I researched, Togo is not a common name among Armenians, and I could not confirm what Togo means in Armenian. There is no profile of Acemyan, not even his birthplace or birth date. Since TOGO didn't answer my questions about his profile and the meaning of his name, we don't have any information besides his name and the date of TOGO's foundation. It is possible to assume that he was born in 1905 or later, and possibly was named after the Japanese admiral if he had his own shop by around the age of 30. What is certain is that nobody in Turkey cares about the origin of TOGO; wearing a pair of leather shoes from this store does not identify someone as an ardent supporter of the famous general’s 1905 naval victory against Russian imperialism. Moreover, if this story was accurate and sufficiently well known, it most likely would have gotten a mention in the film 125 Years Memory. A Turkish-Japanese coproduction that deals specifically with the mutual naval history of both countries.

We are heading to Togo Street now. Except we don’t even know where it is supposed to be. Most sources just say "Turkey" or "Istanbul." Let's look up a few references for its location. We can find three narratives. The first narrative is that the former name of Atatürk Street in Ankara was Togo Street. We can see an example on the Japanese Wikipedia page on Heihachiro Togo. The source is a book published in 2010 by a critic named Ken'ichi Matsumoto titled Why Are There American Military Bases in Japan?. According to Wikipedia, "Ken'ichi Matsumoto states in his book that Togo Street in Ankara was renamed ‘Atatürk Street’ several years ago." Therefore, Atatürk Street, one of the main streets in Ankara, was Togo Street until a few years before 2010. However, Atatürk Street in Ankara has been Atatürk Street since it was established in 1929, and there is no evidence that it was ever named Togo Street. The Atatürk Street claim is hence debunked.

The second is the claim that Togo Street is located in the Old City of Istanbul. This appears in a 2015 book titled The Beautiful Japanese Language That Cannot Be Translated into Foreign Languages by Reiko Durand. Following a description of visiting the Grand Bazaar and other sites in the Old City in Istanbul with her friend, Durand writes:

"One of the main streets is Togo Street. We took a break at a café here and enjoyed authentic Turkish coffee. According to Masayo (Durand’s friend)'s explanation, ‘Togo Street’ was named after General Heihachiro Togo."

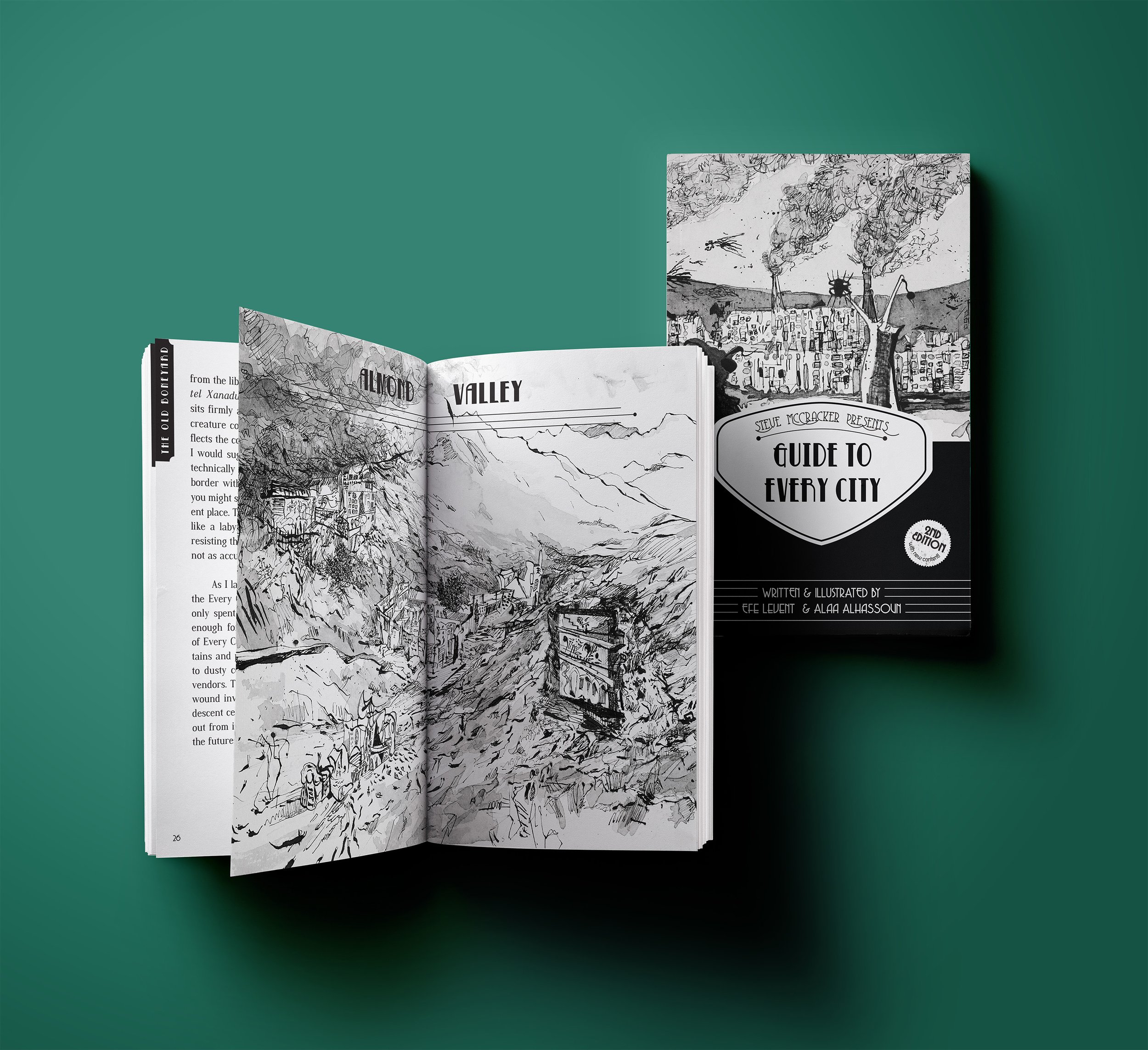

When people in Japan refer to the Old City of Istanbul, they refer to the present-day Fatih district. The areas from Grand Bazaar to Sultanahmet and around Eminönü are where you likely can enjoy Turkish coffee while sightseeing as a tourist. The "main streets" in these areas are Divan Yolu, Alemdar, Bab-ı Ali, Yerebatan, and Ragıp Gümüşpala. Divan Yolu has not changed its name since the conquest of Constantinople in 1453. So it's impossible that this street was ever called Togo Street. Let's look up the previous names of the other streets. I investigated maps of the second half of the 19th century, 1904, 1905, 1914, 1918, 1934, 1941, and 1955. The names of the streets in this district, including the side streets, have remained almost unchanged to the present day. The only street names that have changed are Alemdar, which was initially named Ayasofiya-i Kebir Street, and Ragıp Gümüşpala Street, which was opened in 1964 and integrated some small streets there, so they were never named Togo Street. I also consulted the 2014 map to be sure, but Togo Street does not exist there either. If she is not lying, Durand and her friend Masayo might have visited Istanbul in a parallel world! We have one more fascinating story of her travel to Parallel World Istanbul. She claims they found a shoe shop named Nogi. Let's see her exciting encounter at the Nogi shoe shop:

Hey, hey, hey, look!" Suddenly Masayo shouted loudly. We looked and saw a large shoe store with a sign that read NOGI, which didn't seem to be a Turkish name, or perhaps General Maresuke Nogi? Two young Turkish men heard us saying "Nogi, Nogi" and then spoke to us in English from the next table. "Japanese? Exactly! It's after General Nogi of Japan."

![resim 3 5___Constantinople_vol_I_[...]Goad_Charles_btv1b10100624t_1.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5767ac7e29687f6102b18153/1656583808877-F7Z4PUTX8N21X8VHESC4/resim+3+5___Constantinople_vol_I_%5B...%5DGoad_Charles_btv1b10100624t_1.jpg)

![resim 4 Plan_d'assurance_de_Constantinople___[...]Goad_Charles_btv1b101006347_1.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5767ac7e29687f6102b18153/1656583806804-PKXRCUXE62JDUODRBBUA/resim+4+Plan_d%27assurance_de_Constantinople___%5B...%5DGoad_Charles_btv1b101006347_1.jpg)

Map views of Ayasofya-i Kebir Avenue and smaller streets branching from it

Their stupidity and short-sightedness never cease to amaze me. I take pleasure in the fact that the world is always full of new surprises. Who does think a shop named Nogi comes after a Japanese general when they find it abroad? Then, at the right time, right place, some locals materialise to explain its origin. Which confirms exactly what they want to hear? It seems travel writers have a remarkable ability to encounter the perfect guide at the exact right moment. It's a shock to me, and it will probably come as a shock to you: there is no Nogi shoe shop in Istanbul. We cannot find any traces of a Nogi shoe shop that exists or ever existed. If I believe they are inhabitants of our real world, I can imagine how she came across this story in her brain. She might have known the urban legends of Togo Street, children named Togo or Nogi, and the TOGO shoe shop. So sadly, her memory was not so accurate. Then when she was writing this book, these stories were joined together to give birth to a chimaera of the Togo urban legend: the NOGI shoe shop. Let us not forget the fact that her narrative about Togo Street is very original. Because no one who talks about Togo Street and its variants has ever claimed they saw Togo Street with their own eyes. Moreover, she created the NOGI shoe shop, which no one mentioned before. The meme circulation finally came to life through Durand's pen. The only logical next step now is to open a NOGI shoe shop in Japan, so everything comes full circle as it did for Togo beer.

Another theory is that Toygar Street equals Togo Street. This theory is one of the most popular, as it is capable of providing a detailed location. Again, the Japanese Wikipedia entry on Heihachiro Togo says: "The name of 'Togo Street' is 'Toygar sokağı.' However, Toygar is a Turkish word meaning lark, so it may have nothing to do with Togo." It is difficult to understand because Toygar Street is located next to Aynalıkavak Palace in Istanbul, contradicting the sentence just one line earlier in the same entry, which states that Togo Street existed in Ankara. Anyhow, I like the humble phrase that follows these bold claims: "may have nothing to do with Togo."

Undated magazine clip showing Toygar Street

What is the source of this claim? I found in the edit history of Wikipedia that someone named Tanoshii Oryouri (Fun Cooking) added this claim on October 3, 2013. Further investigation reveals that the image posted as a photo of Togo Street in the April 24, 2006 entry of the blog Natto Life, Go Ahead matches a picture clipped possibly from a magazine on another blog, Class Making JAPAN YOKOHAMA Primary. Unfortunately, as usual, they don't include a proper reference, so I could not find out where this picture comes from. It is an essay written by a student of Tokyo International University. However, nothing earlier mentions that Toygar Street might be Togo Street, so this essay is considered the original source:

I finally found it while asking around through the postman. I had no way of knowing why they named this place Togo Street. I was so fascinated that I snapped away, even though photography is prohibited in the vicinity of Togo Street due to the presence of prisons, police, and military installations. However, I could not find "Nogi Street" at last. I will go back to Istanbul again. I asked the locals to look for "Nogi Street", so I should be able to find it by then. It is sad to see precious historical relics fade away with time. However, I was thankful that Togo Street still remains in a foreign country. In addition, I should mention that "Togo Street" was initially written as TOGOR, but the current residential address is TOYGAR.

We need to respect this student’s vitality to find a street on foot in a country she had never visited before. She was far more sincere than other counterparts, who never tried to find the actual location of Togo Street. I am afraid she could not find Nogi Street and Toygar-Street-which-is-really-Togo-Street, because no such place exists in Istanbul. She would have made better use of her precious time by visiting Aynalıkavak Palace just next to the street instead.

1918 map by Necip Bey showing Toygar Street as Zindankapı Street

So, was TOYGAR Street really TOGOR Street? I think the Turkish pronunciation of Togor is very different from Togo. Anyway, a map drawn by Necip Bey in 1918 shows it as Zindankapı Sokağı, and a map of 1935 shows it renamed Toygar Street. I also visited this street, and it was a back street. Although it is adjacent to the Aynalıkavak Palace and the naval arsenal, it is hard to believe that the Turks, who were "overjoyed" at the Japanese victory, would choose this street to express their jubilation. It would be more reasonable if Donanma street, just in front of Aynalıkavak Palace, was called Togo Street. But this assumption is also refuted because it was called Hasköy street. The student who “discovered” Toygar Street persistently asked around various people where it was located. Perhaps a "kind" local suggested Toygar Street, the most similar-sounding street in his memory. This is a very common occurrence in Turkey. Being asked, the locals try their best to be helpful even if they have no idea. It’s not hard to imagine the locals told her a suitable made-up story that Toygar Street was called Togor in the olden times, to free themselves from the student’s interrogation.

Pictures of Toygar Street taken by the author

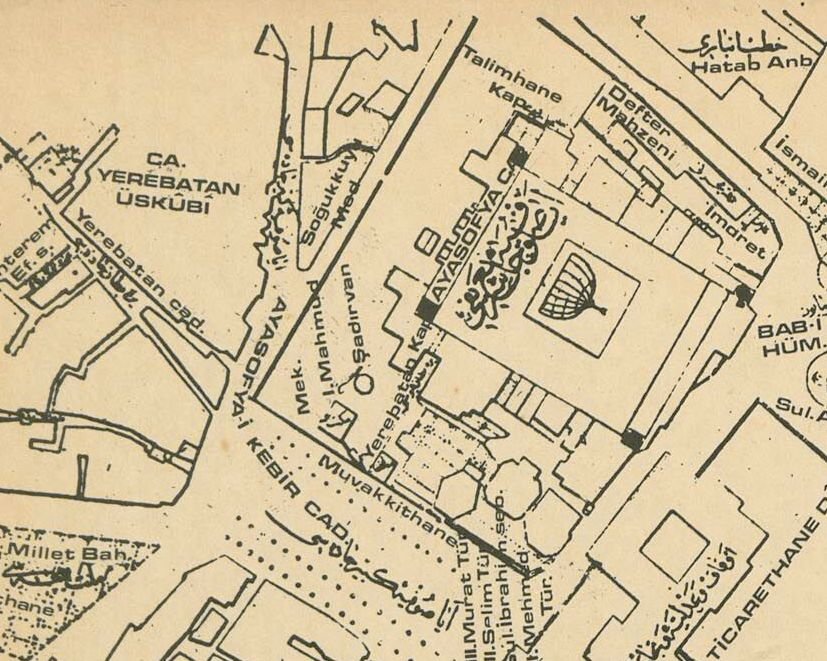

1906 article from The Balkan titled ‘Japanese and Turks’

To make sure, I researched the Ottoman newspapers from several years after the Russo-Japanese War but could not find any reference to Togo Street. On September 4, 1906, a newspaper, The Balkan, published an article entitled Japanese and Turks. The report praises Japan's victory over Russia, mentions that the Ottoman Empire sent an envoy to Japan, that embassies are to be opened in both countries, and that Japanese travelers are now coming to Istanbul. (They joined the congregation in prayer in a mosque. Wow.) Again, I could not find any evidence of Togo Street in any newspapers, despite some of them reporting on the Russo-Japanese War in detail. Also, there were no articles in Japanese newspapers of the same period noting the establishment of Togo Street in Istanbul.

“Now all three theories have turned out false. The claim that the Ottoman Empire, elated by Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese War named a street after Heihachiro Togo is a total hoax. ”

Now all three theories have turned out false. The claim that the Ottoman Empire, elated by Japan's victory in the Russo-Japanese War, named a street after Heihachiro Togo is a total hoax. Like the episode of Halide Edip's son's name, it is a discourse that has been expanded by absorbing the desire among the Japanese for Japan to be globally adored.

So, who started claiming the existence of Togo Street in the first place? It may be impossible to fully identify the source of this discourse, which circulates at the level of gossip. The oldest identifiable reference to Togo Street on Google Books is an interview published by the Japanese magazine The Economist in 1970. Hasegawa, the interviewee, talks about his travel to Turkey and how Turkish people admire Japan. During the interview, the interviewer laments the poor reputation of Japanese people in recent years. Hasegawa goes on to mention Turkey as an example of countries that still admire Japan.

Interviewer: "I heard there's such a thing as Togo Street."

Hasegawa: "That's right. I heard that it is written in elementary school textbooks, and even elementary school children know about Togo and Nogi, while Japanese children do not.

Interviewer: "Today, the Japanese have a bad reputation internationally. Unfortunately..."

Hasegawa: "In Turkey, they say Japan has become a champion among Asians and a splendid country. When they say that Japan has grown, I thought they were referring to the third-largest GNP in the world. But they didn't mean that; they meant the Meiji Restoration; Japan did a very admirable thing with the Meiji Restoration because they did a great deal for education."

It is very doubtful that they taught Togo in elementary school history classes in the 60s. It is well known that history education in Turkey has a very heavy emphasis on national history. Some point out that only 5-10% is devoted to world history in textbooks. And I am sceptical that Hasegawa talked about the Meiji Restoration during his trip. I suppose very few people knew about the Meiji Restoration in Turkey in 1970. Reading the context of this interview, we can safely assume the interviewer wanted to hear that Turkey likes Japan, and Hasegawa gave the desired answer.

Although this interview is probably the first appearance of Togo Street in print media, this discourse had circulated among some people for much longer. These discourses always talk about Togo Street and Turkish textbooks. From the very first point, it takes the form of rumour, and they never provide any clear evidence for their existence. It is also important to note that the journalist's laments about Japan’s declining popularity represented the popular sentiment in the 1970s when the high economic growth of Japan soured relationships with countries like the USA. It is understandable to take pride in the rapid economic growth of Japan, which has revived from the rubbles and ashes of WW2. It was an overwhelming effort to rebuild the country and grow to be the third-largest GNP country in such a short time, even if the situations of international politics and economics allowed it to be so. However, the reputation they got was that of ”economic animals.” From its inception, Togo Street reflected the desire of Japanese people to believe that Japan was well-liked by foreigners. It is a soothing myth, not unlike the medieval Europeans' belief that there was a Christian land of Prester John somewhere in Africa or Asia, who would save them from the Muslims attacking Europe.

Cover of Anti-Japan Nation Japan

Let’s see how this discourse was handed down. Google Books reveals that the books mentioning Togo Street frequently appear from around 2000. As far as I can find, before the 2000s it only appeared in a 1975 report by the Japan Youth Overseas Mission, a project of the Cabinet Office; a 1985 book, Anti-Japan Nation Japan: Home run to clear up national disgrace; serious trial proceeding, by prominent right-wing critic Futaranosuke Nagoshi; and in the 1990s in magazines such as the Liberal Democratic Party's Monthly Liberal Democrat; a magazine of conservative opinion, Gentlemen!; and in Fellow Countrymen. The reason we only see books from the 2000s could be because the Google Books database doesn’t record earlier publications. However, we can assume it reflects the actual situation with some degree of accuracy, considering the authors' backgrounds and the movement of right-wing intellectuals during this period. The books in which Togo Street is mentioned can be categorised as follows: (1) history books with a right-wing narrative, (2) educational books derived from (1), (3) books glorifying Japan and the Japanese, and (4) books that harbour hate speech.

The earliest book that falls into type (1) was a history book titled Togo Heihachiro: The Meiji spirit that revitalised modern Japan, published in 1997 by Mikihiko Okada, a senior fellow at the Japan Center for Policy Studies. Subsequently, Ren Yasumura’s Silly Diplomacy, Sad Japan (2001), and History of Japan to be Handed Down to Our Children and Grandchildren (2005) by Takanori Nakajo & Shoichi Watanabe. These authors are right-wing intellectuals who criticise postwar Japanese history education that critically teaches prewar Japan by emphasising its belligerent role in World War II. These intellectuals refer to this historical narrative as the "Masochistic View of History" or "Comintern View of History (!)". Their own books were written to emphasise Japan's "glorious modern history" from a revisionist perspective. This revisionist narrative achieved wide acceptance in Japanese society with Yoshinori Kobayashi's bestseller manga Gomanism Manifesto, which condemns post-war education as leftist brainwashing and depicts Japanese soldiers and officers as cool heroes, not war criminals. In this rise of right-wing thought and its currents, Togo Street is used in the context of the world's recognition of a "strong and brilliant" Japan.

Citizens' Association against Zainich Privilege had a demonstration in front of a Korean school in Kyoto in 2010. Some of them got convicted of forcible obstruction of business.

All of the educational books in category (2) are remarkable for the frequent use of an unknown word Togo Sokata (トーゴー・ソカタ). Supposedly, it is a misreading of the Japanese writing of Togo Sokaku (トーゴー・ソカク), which first appeared in Nagoshi’s 1985 book, then Uesgi’s book and one of their textbooks. They are written by people involved in the "Japanese Society for History Textbook Reform," which became increasingly active during the mid-2000s in advocating the incorporation of revisionist historical discourse into school textbooks. It includes the 1985 book by Nagoshi mentioned above, Chitoshi Uesugi’s Summary: Textbook Issues and Education Trials (1990), Nobukatsu Fujioka’s Rating History Textbooks (2000), and Kanji Katsuoka’s The Russo-Japanese War from the Perspective of Textbooks: Is This OK, Japanese Textbooks? (2004). In these books, Togo Street's discourse of "great Japan is recognised by the world" is blatantly used for political purposes. It wouldn’t raise any alarms if they were just about celebrating Japan’s past glory. However, it is chilling to see Togo Street come up next to Nanjing Massacre denial. The ultimate goal of these books is to abolish Article 9 of the current Japanese Constitution, which forbids war. They believe that what they call the "Masochistic View of History" is an obstacle to the abolition of Article 9.

Their political activities bore fruit later, leading to the publication of revisionist school textbooks. (Although the adoption rate for these books remained under 0.1%, and their 2020 revised edition could not pass inspection.) They also achieved some success in the area of moral education, another front for them. From this point on, their perspectives began to appear in books that promoted the moral values of the Japanese. (A troubling fact: Japanese educators love such books for some reason.) This is category (3), which includes Durand Reiko's book mentioned above, Yoshinao Sato’s This Is How Japan Became a Country Trusted by the World (2014), Shoichi Watanabe’s The Moral Sense of the Japanese (2017), Osamu Miyata’s Japan, the Only Hope of Islam (2017), and others. It is ludicrous to see them talk about morals and trust when they blatantly lie about the existence of Togo Street as a warm-up act for genocide denial.

“It is ludicrous to see them talk about morals and trust when they blatantly lie about the existence of Togo Street as a warm-up act for genocide denial.”

Interestingly, Togo Street is written in katakana in these books (トーゴー通り), which was rarely seen in (1) and (2), becoming catchier and more depoliticised on the surface than its kanji counterpart (東郷通り). These authors, except for Watanabe, are consultants and former broadcasters who have not actively devoted themselves to right-wing speech activities. They may be naive nationalists (and maybe even naive racists), but they are not active participants in the discourse movement by right-wing intellectuals. Instead, they are simply profiteers from a parasitic business that feeds the growing desires and insecurities of Japanese society.

In the last category (4) is a book by Takufumi Genkotsu, The Fist, Anti-Japan Ideology: the Truth of History (2013). The title sums it all up, so I will not go into detail. This book explains how the Japanese have dealt with the Koreans, who are said to have accumulated anti-Japan ideology. This work adds racism to the historical revisionist ideology described in (2) above. The discourse of Togo Street is now used to criticise Koreans, who are pegged as anti-Japan by Japanese right-wingers. In this kind of book, they emphasise that foreigners love and respect Japan except for the stubborn Koreans and Chinese, who are wrong and deserve to be discriminated against.

“The discourse of Togo Street was born out of the desire for Japan to be respected by the world against the “Japan Bashing” during the country’s high-growth period. ”

The discourse of Togo Street was born out of the desire for Japan to be respected by the world against "Japan Bashing" during the country’s high-growth period. It started to have a ring of truth as it circulated among right-wing intellectuals and politicians. It was further used as a political tool for historical revisionism and intervention in education. It has now become widely believed in Japanese society and has entered mainstream discourse by the efforts of right-wing intellectuals and the power of the Internet. In the early 2000s, people called the "Internet Right Wing" began to appear, and racist comments increased against the Zainichi (Koreans in Japan). A far-right racist group called "Citizens' Association against Zainichi Privilege" was formed in 2006 and began taking to the streets. The TV and publishing industries saw a surge in programs and books glorifying Japan, a trend that simultaneously led to hate speech books taking over the shelves of bookstores. These coincided exactly with the spread of the Togo Street narrative.

Finally, why does a relatively broad population segment currently accept this discourse? First, it is necessary to understand the dichotomous "pro-Japan / anti-Japan" worldview that vaguely exists in Japan. In Japan, foreign countries are often described as "pro-Japan" or "anti-Japan." This concept does not have an official definition, and its scope changes according to the sentiments of Japanese nationalism at any given time. For example, Turkey is basically classified as a pro-Japan country. One of the "pro-Japan" episodes that support this is Togo Street. If only the concept of a "pro-Japan" country existed, it would not necessarily be harmful, but the problem is the existence of the counter-concept of anti-Japan countries.

However, even if a country is recognised as pro-Japan, it does not mean that it will be regarded as a friendly country forever. For example, Ukraine was considered a pro-Japan country by Japanese nationalists until recently. But this changed rapidly when President Zelensky referred to Pearl Harbour in his speech to the U.S. Congress. Later, in a public relations video produced by the Ukrainian Foreign Ministry, a picture of Hirohito was shown alongside Hitler and Mussolini as fascist leaders. Ukraine faced a backlash, then took the video down and apologised. Some Japanese internet users started shaming Ukraine as an anti-Japan traitor and even stated they would support Russia instead. What is required of pro-Japan countries ultimately is the very egocentric function of eternally praising and respecting Japan and beating up anti-Japan countries along with Japan's far-right.

In recent years, there has been some discussion in Japan that "group narcissism” can explain these societal trends. Group narcissism is a state in which people with low self-esteem try to preserve their pride by believing that their group is superior and that others recognise its superiority. Japan's self-praise as "Japan is awesome" is a typical example of group narcissism. Let me show you an example of a TV program that demonstrates this childish narcissism in a nutshell. In this video, we see a group of Chileans overjoyed when they see a Japanese cab automatically open its doors as if a saviour has appeared in front of them. One of them even falls on his knees in an excessive performance of enthusiasm. Yes, it is a cringe-inducing image, but such programs were produced and broadcast in Japan at one time.

I was born in the exact period of the collapse of the Japanese bubble economy and the following Asian Financial Crisis, the so-called lost ten years. (It became the lost thirty years now.) Back in the day, Japan had the world’s largest economy and was called “Japan as number one.” Nobody could ignore Japan in many fields. However, the sound of Gion Shoja bells echoes the impermanence of all things; the proud do not endure, they are like a dream on a spring night. The Japanese economy has declined now. The honours of great Japanese companies have vanished. ASEAN is no more a group of third-world countries. Taiwan grew up to be the most advanced democratic country in Asia. Korean electronic products are far better than Japanese. No need to even talk about the significance of Chinese growth in the last fifteen years. During this period, the Japanese economy remained stagnant. It is undeniable that Japan’s international importance has declined and was replaced by other Asian counties. It is not surprising that this trend has hurt national pride. Some started to seek a way to escape from this bitter reality into group narcissism. They merged their identity into the nation-state. As long as Japan is great, their personal greatness will also be ensured, at least in their mind. Togo Street would be one of the most suitable myths to reconfirm Japan’s military greatness. It is also a response to dissidents who criticise Japanese militarism. They can say Japan is respected, and that foreigners admire her military.

I also have the memory of having this kind of experience when I was a teenager. I read Gomanism Manifesto one day—I cannot remember why. It was fun and convincing enough for a naïve teenager interested in world affairs. For a silly boy who knew nothing, a lot of hate speech and false information on the internet seemed plausible. I felt like I knew the truth of the world. It didn’t take long for me to believe WW2 was a war of defence, and those who criticised the Japanese imperial army were traitors. It seemed reasonable to me that certain groups tried to make Japan decline, and Koreans tried to manipulate Japan from behind. I thought those who didn’t recognise Japanese greatness were stupid and everybody needed to fight to protect our motherland. It was thanks to my teacher at the cram school that I changed my mind. He was an anarchist who persuaded me that nationalism and racism were nonsense and uncool. I learned that concepts like nation and race were social constructs, not solid facts. I realised how the right-wing discourse on the internet was baseless through learning history. Those who told me the world's truth on the internet were not sages but nitwits who believed themselves wise by disseminating nonsense that could be refuted by the knowledge I learned in high school. The world was complicated and deep. Looking back, I didn’t have any knowledge and critical distance to the information I received. I had the fortune of attaining broader and more accurate knowledge to criticise narratives on the internet. I was young and not like elder internet right-wingers, who felt the decline of Japanese economics and its honour in their lives and jobs. I think this was the biggest reason I could abandon this idea. I could absorb different thoughts, as I had absorbed nationalist propaganda. I know my example is not universal, but I believe that having a supportive environment can have significant importance in challenging existing worldviews.

Finally, let me tell you about the rabbit hole that led me to Togo Street. When I was in Turkey in 2013-2014 as a student at TÖMER, a Turkish language school, I saw a tweet that referred to Togo Street, saying:

“Turkey still feels indebted to Japan for the rescue of the Erutouru エルトウール [maybe Ertuğrul]. The "Ertouru Rescue Incident" is even in Turkish textbooks. Naturally, Turkey is a pro-Japanese country, and "Togo Street," "Nogi Street," and "Yamamoto Street" still exist in the city of Turkey [???].”

More Articles

I have no idea what “the city of Turkey” means, but this might not be so important for the author. As I explained above, its location is not a serious problem because even its existence is not crucial; the most critical point is Turkey being a pro-Japan country. The remarkable point of this tweet is “Yamamoto Street.” This is probably Isoroku Yamamoto, the famous Japanese general during WW2. I think Yamamoto is relatively young compared to Togo and Nogi. He was born in 1884 and graduated from a naval academy in 1904 during the Russo-Japanese War. It is hard to imagine that the Ottomans named a street after a young midshipman even though he fought in the Battle of Tsushima under the command of Admiral Togo. His career flourished in WW2, which makes it even less likely that a street would be named after him, since the country joined the Allied war effort in February 1945. So it is far more nonsense put to him in this line, but it seems it is not for the author of the tweet.

Anyway, I had time and energy to try to stir up a bit of controversy—maybe I had some nasty desire to make fun of internet right-wingers. So I asked him: “Hello. I am currently living in Turkey. I want to know the exact locations of those streets because I’ve never heard of them here. Could you give me information because it seems you know about them very well?” He kept silent for three days or so, then suddenly apologised for giving ambiguous information. But he didn’t relent on the existence of Togo Street until the end. During the three days, my tweet got a lot of traction (which is very unusual for my account), and it caused a dispute: does Togo Street exist? No one knew Turkish or Turkey well, so they settled for the customary internet melee. For a long time, the words said to me by one person have stuck with me: “But you don’t really know that Togo Street DOESN’T exist, do you?” Right. I didn’t have any evidence, even if I firmly believed in its non-existence. I didn’t know Istanbul well and had no techniques to investigate it. However, I am a PhD student in Ottoman History now, so I have these techniques for historical investigations, such as Turkish, Ottoman, and some reading ability of historic documents. Now that I have investigated, I can finally give my answer. Now I can confidently say that Togo Street and its variants don’t exist in Turkey. They were just a delusion born of a desire of Japanese nationalists who wanted to think that foreigners respected them.

“Now I can confidently say that Togo Street and its variants don’t exist in Turkey. They were just a delusion born of a desire of Japanese nationalists who wanted to think that foreigners respected them. ”

Until here, we looked at the history and usage of the Togo Street narrative. It is easy to see that it has always been hearsay from its appearance in 1970 to the present. This rumour emerged from a desire to see Japan being recognised by the international community as a respected country. It then gained the aura of truth by going through a chain of references. It is quite natural to believe this myth when it has been repeated by various Middle East experts, some of them writing in peer-reviewed journals, and even an ambassador. But as we see, the existence of Togo Street was always ambiguous, even to those who claim to be certain of its existence. Asking whether there is a Togo Street in Istanbul is really a different question, Is Turkey pro-Japan? Maybe yes. If you ask Turkish people whether they like Japan, most of them will say yes. But it’s not like our right-wingers think; it’s just on the level of Geisha, Samurai, Harakiri, Yakuza, and maybe Anime. (We cannot blame them because we also like Turkey and know just kebab, Cappadocia, Togo Street, and “men with a turban on a camel in the desert.”)

Perhaps a better question is to ask: why do they always talk about Togo Street when we have several Turkish street names related to Japan? Kushimoto Street in Mersin is named after a village that rescued Turkish sailors during the Ertuğrul Incident. Shibuya Street in Istanbul is dedicated to celebrating the sister-city affiliation with the Shibuya district of Tokyo. In Beykoz, there is a street named Yarbay Yukichi Tsumura, a commander who saved and brought Turkish prisoners of Russia to the Ottoman Empire during WW1. Both a street and a school in Van and a park in Istanbul have the name of Dr. Atsushi Miyazaki, who had died during the rescue mission for the 2011 Van earthquakes. It is safe to say those two men deserve to be called heroes. Even the locals in Beykoz don’t know who Yukichi Tsumura is and the fact that the name of the street has changed to Yarbay Yukichi Tsumura; at least the Turkish government and the municipality recognize what this man has done. Dr. Miyazaki is more of a contemporary example and is well known, as his sacrifice has been reported broadly in Turkey.

These episodes can be used as proof of Turkey being a pro-Japan county. However, I have hardly come across their names from the mouths of those who talk about Togo Street. It is understandable we don’t come across those names in the books because those streets are relatively new. However, even on Twitter only a very small number of accounts talk about Tsumura. All of them say, “Oh, I didn’t know him.” I could not find anyone who mentioned him more than twice. Miyazaki's references are in almost the same condition. For the internet patriots, it seems those real streets are less attractive than the imaginary Togo Street. I assume it is because neither Dr. Miyazaki nor Tsumura is a national war hero. Togo, on the other hand, has a crucial role in the Japanese right-wing discourse, because they can show off the glorious Japanese army’s history through his achievement in the Russo-Japanese War.

There is a very eloquent entry at the Japanese Society for History Textbook Reform, which criticises conventional textbooks as a “historical view subjected to China and Korea.” They continue their textbooks with an assertion to “correctly evaluate the world-historical significance of the victory in the Russo-Japanese War and not position it as the beginning of Japan’s domination of Asia, but rather as the beginning of new tensions with the Western Powers,” then conclude “The Russo-Japanese War was one of the climaxes of Japan’s journey of modernization since the Meiji Restoration, a world-historical event that gave hope and courage for independence to people around the world.” This is the “cool war story”, that they want to use to tilt Japanese public opinion in favour of the constitutional change, their ultimate goal.

Although I made an effort to prove the non-existence of Togo Street and narratives of its variant, I am so sure they will keep the belief of Togo Street even after this article is published, because most of them hardly read anything written in a foreign language. Even the few who do will doubt or just ignore it because Togo’s role will remain and even be strengthened by group narcissism. In this one year, the value of the Japanese yen fell from 110 to 134 against the USD. Rising taxes and energy bills strain peoples’ livelihoods and we have no clue how to solve any of these problems. Some need psychological drugs to avoid these painful realities. Therefore, Togo Street will remain in the hearts and minds of Japanese people until they develop a healthier sense of confidence and one day realise they don’t need this kind of groundless rumour. Or else we will find ourselves having to refute new sightings of Togo Street in the future.